Few bats capture the imagination quite like the horseshoe bats. Named for the intricate, horseshoe-shaped noseleaf that frames their faces, these species are among the most evolutionarily distinct mammals in Europe. Their unique facial structures act as an acoustic lens, focusing high-frequency echolocation calls with extraordinary precision. The result: a sonar system so sensitive it can detect the flutter of a single moth wing in complete darkness.

Jersey is home to two confirmed species — the lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) and the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum). Together, these bats represent the island’s connection to a lineage that dates back over 30 million years — one that has survived ice ages, habitat loss, and modern change through extraordinary sensory adaptation.

GREATER HORSESHOE BAT (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum)

Elegant, powerful, and unmistakable, the greater horseshoe bat is one of Europe’s largest and most charismatic bat species. With a wingspan of up to 40 cm and a body the size of a small mouse, it roosts in warm caves, stables, and barns, preferring landscapes rich in pasture and hedgerows.

Taxonomy & History

Described by Schreber in 1774, R. ferrumequinum is the largest of Europe’s horseshoe bats and the type species of the Rhinolophidae family. Once widespread across the British Isles, it suffered severe population declines during the 20th century — disappearing from most of Britain by the 1970s. On the European mainland, strongholds remain in western France, Iberia, and parts of the Balkans. Occasional records from Jersey suggest that individuals still cross from Normandy, where the species remains relatively stable.

Ecology & Behaviour

Greater horseshoe bats are quintessential edge-habitat specialists. They forage over grazed pastures, orchards, and hedgerow-lined lanes, using their highly directional 83 kHz calls to detect dung beetles, moths, and crane flies. Their flight is slow and deliberate, often close to the ground or just above vegetation, and they frequently return to habitual feeding areas — a behaviour known as “traplining.”

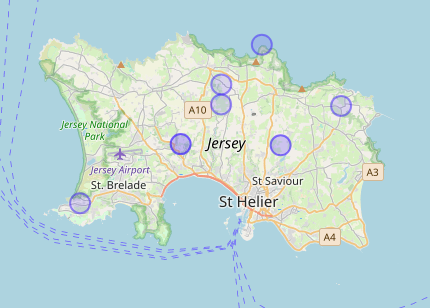

Roosts are traditionally located in warm, undisturbed buildings for maternity colonies and cool caves for hibernation. Each colony can persist for decades; individuals show strong roost fidelity and may live over 30 years. In Jersey, the species has been recorded intermittently in acoustic monitoring datasets and occasional field observations, but no confirmed breeding colonies have been found to date, however, there have been an increasing number of records suggesting there are roosts on the island.

Conservation

The greater horseshoe bat is listed as Least Concern (IUCN) globally but is of High Conservation Concern in France, and remains a UK Priority Species under the Habitats Directive. Its survival depends on maintaining interconnected landscapes of grazed pasture, hedgerows, and cattle dung — vital for its beetle-rich prey base. Declines across northwest Europe have been linked to pesticide use, agricultural intensification, and loss of traditional roost sites.

Research Notes

Research on R. ferrumequinum has been pivotal to understanding bat ecology and conservation. The long-term study by Professor Roger Ransome in Devon (1960s–2000s) remains one of the most comprehensive bat population projects ever undertaken, revealing multi-generational roost fidelity, energy budgeting, and the species’ sensitivity to temperature and prey fluctuations. Jones & Rayner (1989) and Jones et al. (1993) documented its precision flight and prey detection strategies, showing how its noseleaf system evolved to detect low-intensity target echoes.

More recent research by Bontadina et al. (2002) in Switzerland and Knight & Jones (2009) in Wales demonstrated the species’ reliance on mosaic landscapes — a combination of pasture, woodland edge, and hedgerow — for foraging efficiency. Genetic work by Rossiter et al. (2000) further highlighted strong philopatry and limited female dispersal, making local colonies particularly vulnerable to fragmentation.

Fun Fact

Greater horseshoe bats have a distinctive social “song” — a quiet trill exchanged between roost mates — that helps them recognise familiar individuals and maintain group cohesion.

LESSER HORSESHOE BAT (Rhinolophus hipposideros)

Tiny, delicate, and wonderfully intricate, the lesser horseshoe bat is one of Jersey’s most distinctive residents. Barely the size of a plum and weighing only 5–9 grams, it hangs free when roosting, wrapping itself in its wings like a miniature umbrella.

Taxonomy & History

Described by Bechstein in 1800, R. hipposideros is one of the smallest European bats and among the oldest lineages of the Rhinolophidae family. Once common across the Channel region, its populations crashed dramatically in the mid-20th century due to pesticides and roost disturbance. In recent decades, conservation initiatives across the UK, Ireland, and France have seen remarkable recoveries.

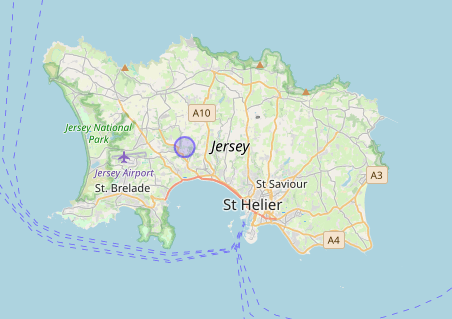

In Jersey, the lesser horseshoe bat has one confirmed hibernation roost, located in a part of the Jersey war tunnels.

Ecology & Behaviour

Lesser horseshoe bats prefer sheltered, humid habitats — woodlands, river valleys, and orchards — where they forage close to vegetation for small moths, midges, and craneflies. Their characteristic echolocation calls (~110 kHz) are continuous, allowing them to detect minute movements in cluttered environments. Their flight is agile yet slow, enabling precise manoeuvring in dense cover.

Roosts are typically found in old stone houses, attics, or cellars, often with maternity colonies numbering 30–150 individuals. Winter roosts are usually in caves, tunnels, or disused mines.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) but Vulnerable in France, the lesser horseshoe bat has made one of the great conservation comebacks of recent decades. In Britain and Ireland, populations have doubled since the 1990s thanks to strict roost protection and agri-environment schemes. In Jersey, the species’ continued presence is a testament to local conservation work — including roost safeguarding, acoustic monitoring, and habitat restoration led by the Jersey Bat Group.

However, threats remain: renovation of old buildings can destroy roosts, increasing light pollution may fragment dark corridors, and pesticide use still reduces prey availability.

Research Notes

The lesser horseshoe bat has been the subject of extensive ecological and conservation research. Bontadina, Schofield & Naef-Daenzer (2002) used radio-tracking to demonstrate the importance of continuous tree cover and hedgerows linking roosts to foraging grounds. Knight & Jones (2009) confirmed that colonies prefer foraging routes less than 10 m wide, underscoring how even narrow gaps in vegetation can act as barriers. Ransome & Hutson (2000) reviewed its dramatic 20th-century decline and highlighted the crucial role of stable microclimates in maternity roosts.

Recent studies by Dietz & Kiefer (2016) and Ancillotto et al. (2018) explored acoustic and thermal constraints, showing how R. hipposideros selects roosts with consistent humidity and minimal draughts — a key reason why renovated roofs or modern insulation can make traditional roosts unsuitable. Genetic work by Rossiter et al. (2000) and Davidson-Watts & Jones (2006) further revealed fine-scale population structure and strong site fidelity, suggesting that each colony represents a vital conservation unit.

Fun Fact

The lesser horseshoe bat’s distinctive “hanging cloak” posture — wrapping its wings completely around its body — isn’t just for warmth. It helps maintain humidity and muffles sound reflections, allowing stealthy prey detection in tight spaces.

Further reading

Jones, G. & Rayner, J.M.V. (1989) Foraging behaviour and echolocation of wild horseshoe bats Rhinolophus ferrumequinum and R. hipposideros (Chiroptera, Rhinolophidae). Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology, 25, pp. 183-191.

Jang, J.E., Byeon, S.Y., Kim, H.R., Kim, J.Y., Myeong, H.H. & Lee H.J. (2021) Genetic evidence for sex-biased dispersal and cryptic diversity in the greater horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. Biodiversity and Conservation, 30, pp. 847-864.

Wright, P.G.R., Kitching, T., Hanniffy, R., Palacios, M.B., McAney, K. & Schofield, H. (2022) Effect of roost management on population trends of Rhinolophus hipposideros and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum in Britain and Ireland. Conservation Evidence Journal, 19, pp. 21-26.

Dzięgielewska, M., Ignaszak, K., Olejnik, P. & Małecki, Ł. (2025) The first observation of the Lesser Horseshoe Bat Rhinolophus hipposideros (Bechstein, 1800) outside the northern limit of occurrence in Europe. The European Zoological Journal, 92(1), pp. 1020-1027.

Working to protect and conserve Jersey’s native bat species through research, education, and community involvement.

Join our mailing list to receive updates about bat walks, training, and events.

2025 Jersey Bat Group. All rights reserved.