If pipistrelles are the generalists of the bat world, then Myotis bats are the specialists — a diverse and finely tuned group adapted to specific habitats and hunting styles. Their name comes from Greek, meaning “mouse-eared,” and across Europe they represent one of the largest and most complex bat genera.

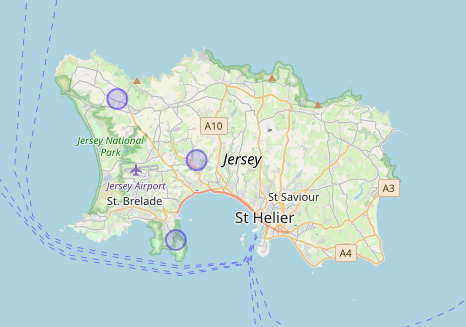

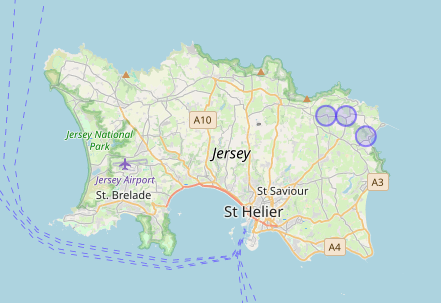

In Jersey, six Myotis species have been recorded so far: the whiskered bat (Myotis mystacinus), Brandt’s bat (Myotis brandtii), Natterer’s bat (Myotis nattereri), Daubenton’s bat (Myotis daubentonii), Geoffroy’s bats (Myotis emarginatus) and the exceptionally rare Alcathoe bat (Myotis alcathoe). Each is a subtle specialist, adapted to a different ecological niche — from gleaning insects off leaves in woodlands to skimming prey from the surface of ponds and reservoirs.

Let’s meet Jersey’s mouse-eared bats.

WHISKERED BAT (Myotis mystacinus)

The whiskered bat is one of Jersey’s smallest and most secretive bat species, and also one of the hardest to identify. At first glance, it looks almost identical to Brandt’s bat, but close inspection — or genetic analysis — reveals subtle differences in fur texture and dental structure.

Taxonomy & History

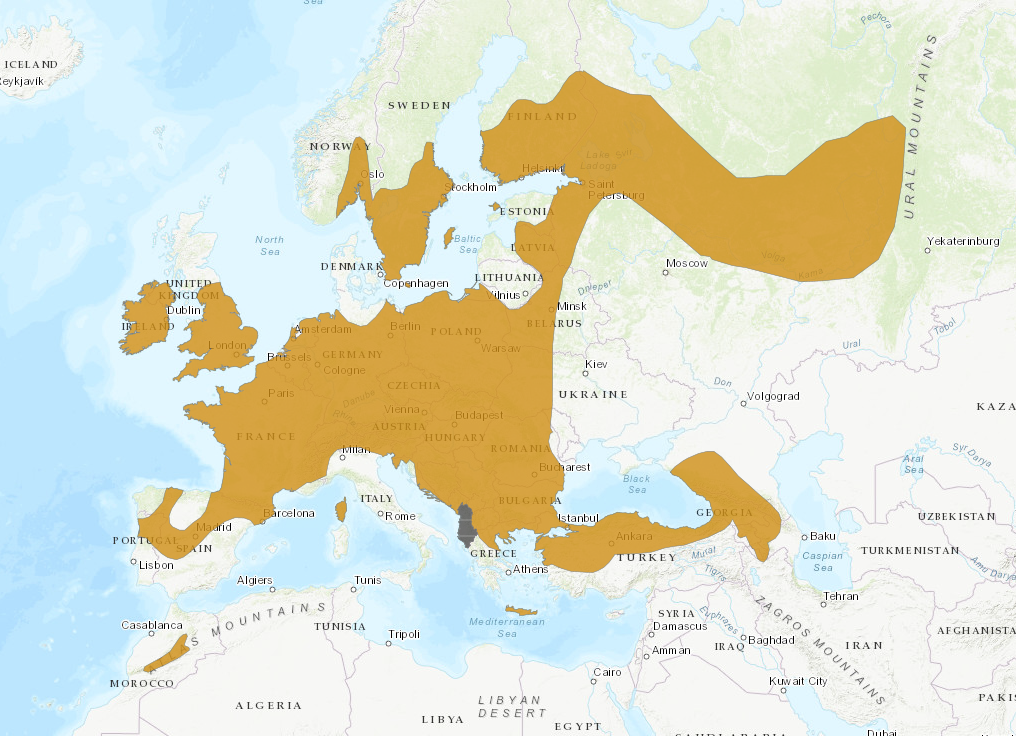

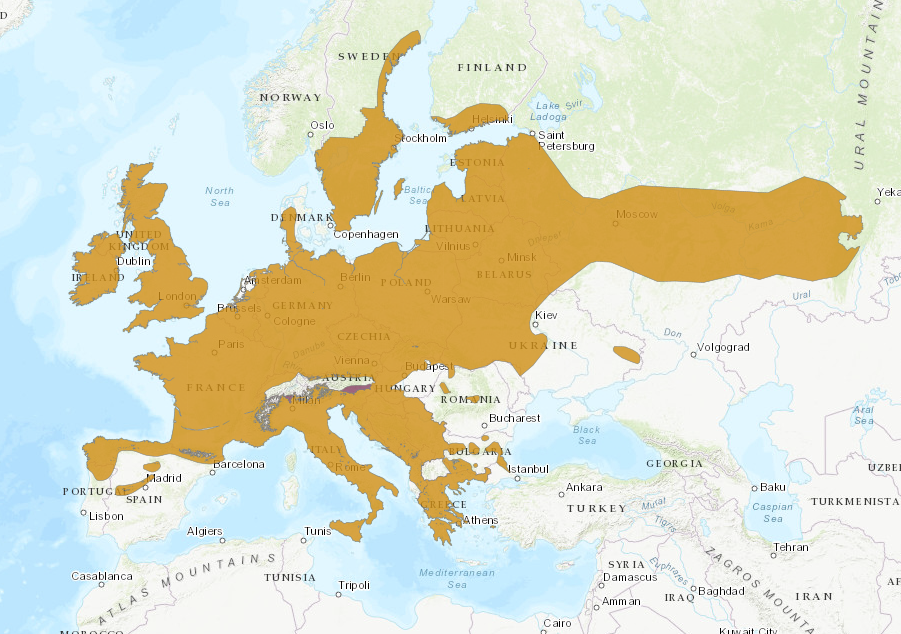

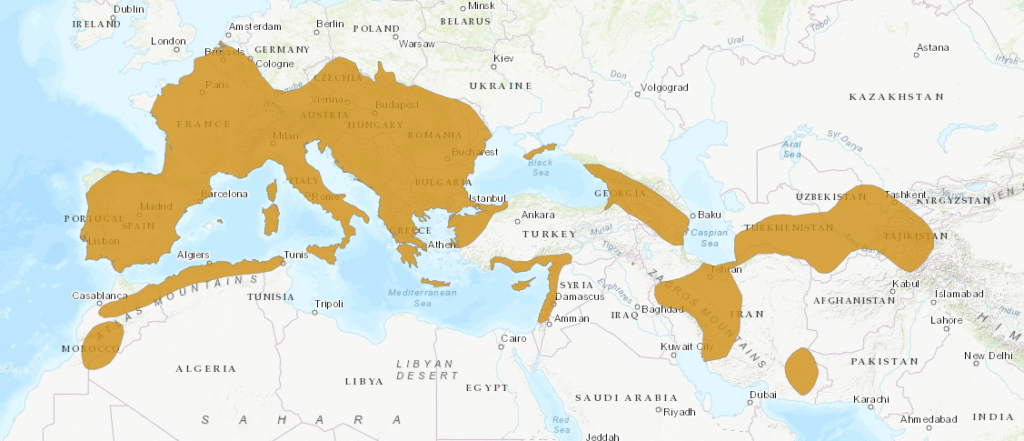

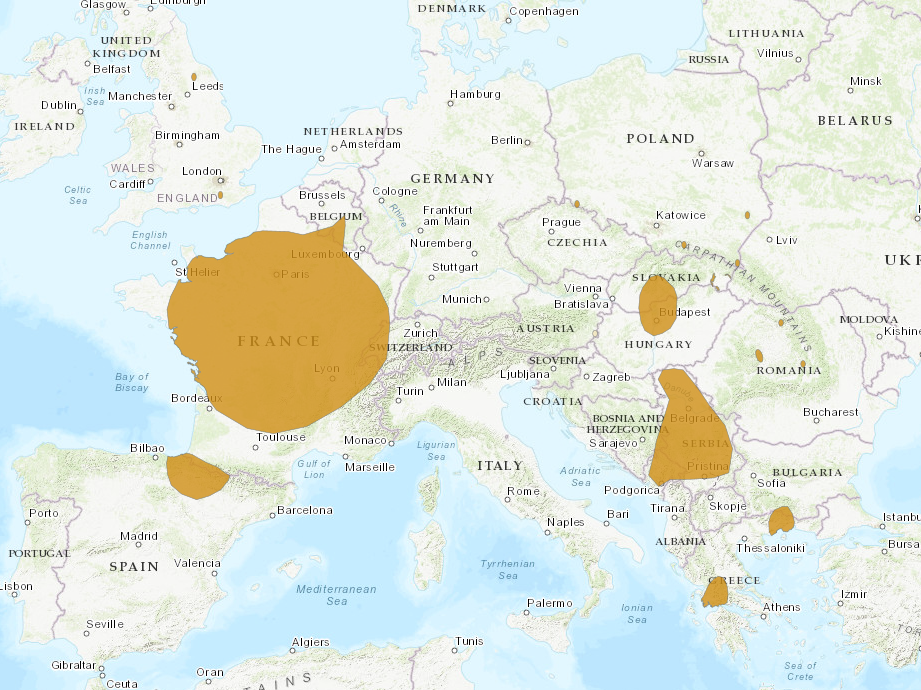

Described by Heinrich Kuhl in 1817, the whiskered bat was long confused with Brandt’s and Alcathoe bats until the 1970s, when detailed morphological work distinguished them. Today, it is recognised as one of Europe’s most widespread Myotis species, found from Iberia to Scandinavia.

Ecology & Behaviour

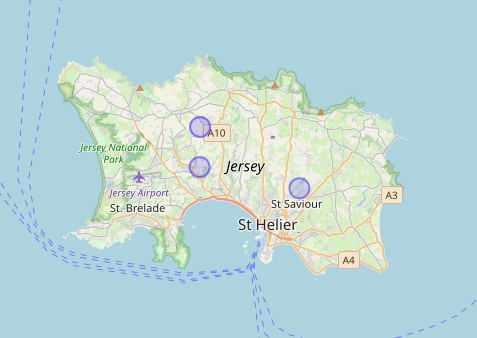

This small bat (weighing 4–8 g) typically roosts in tree holes, old buildings, and crevices, and forages along woodland edges, hedgerows, and riparian zones. It feeds mainly on small moths, caddisflies, and midges, hunting close to vegetation with agile, fluttery flight. In Jersey, it is occasionally detected during woodland acoustic surveys, though likely under-recorded due to overlap with Brandt’s bat calls.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) and considered widespread in France, but vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and the loss of mature woodland. In Jersey, its presence indicates healthy woodland and hedgerow networks that provide foraging corridors and roost opportunities.

Research Notes

Over the last two decades, the whiskered bat has become a model species for studying cryptic diversity within European Myotis. The pivotal work of von Helversen, Heller & Mayer (2001) formally separated mystacinus, brandtii, and alcathoe using molecular and morphological evidence, highlighting how multiple species had been hidden under one name. This taxonomic refinement was consolidated by Dietz, von Helversen & Nill (2009), whose illustrated field guide provided diagnostic features and acoustic parameters that remain the standard for field ecologists. Subsequent genetic studies by Bogdanowicz, Hulva & Ruedi (2012) traced postglacial colonisation routes, showing that whiskered bats expanded northwards from southern refugia after the last Ice Age. Behavioural observations by Lučan et al. (2010) revealed that M. mystacinus favours riparian corridors and woodland margins, displaying flexible roosting and foraging patterns — traits that likely explain its wide European distribution.

Fun Fact

Its name, mystacinus, means “moustached” — referring to the fine whisker-like hairs on its face, which help it sense nearby objects while flying close to vegetation.

BRANDT’S BAT (Myotis brandtii)

Slightly larger than the whiskered bat, Brandt’s bat is another elusive woodland species. It shares similar habits but tends to prefer denser vegetation and cooler microclimates.

Taxonomy & History

Named after the 19th-century Russian naturalist Johann Friedrich Brandt, this species was once thought to be the same as the whiskered bat until separated in 1970 based on morphological and genetic differences.

Ecology & Behaviour

Brandt’s bat forages primarily in woodland and riparian habitats, catching small flies, moths, and lacewings in cluttered airspace. It roosts in trees and buildings, often in small colonies. In Jersey, records are few, but acoustic data suggest its presence in mixed woodland and valley habitats.

Conservation

Classified as Least Concern globally, and stable across France. However, like the whiskered bat, it depends heavily on old-growth trees and a mosaic of woodland and open foraging areas. Light pollution and the removal of hedgerows can reduce feeding opportunities.

Research Notes

Brandt’s bat has drawn international attention because of its extraordinary longevity. The genome study by Seim et al. (2013, Nature Communications) linked its 40-year lifespan to unique DNA-repair and metabolic genes — insights now used in ageing research well beyond chiropterology. Taxonomically, von Helversen et al. (2001) confirmed its distinctness from M. mystacinus and M. alcathoe, and Dietz & Kiefer (2016) later refined acoustic and biometric methods that allow reliable field identification. Ecological studies by Rydell and colleagues (1996–2002) described how Brandt’s bats exploit densely vegetated woodland and riparian zones, their slow, highly manoeuvrable flight adapted for cluttered foraging. Together, these findings portray a species superbly evolved for longevity and precision hunting in complex habitats.

Fun Fact

It is the “Methuselah” of bats — pound for pound, one of the longest-living mammals on Earth.

NATTERER’S BAT (Myotis nattereri)

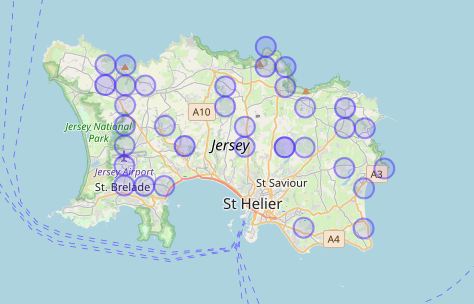

The Natterer’s bat is one of the most fascinating species in Jersey, known for its quiet, precise foraging style and its ability to take insects directly off vegetation. It is also one of the few species confirmed breeding on the island.

Taxonomy & History

Described by Heinrich Kuhl in 1817 and named after the Austrian naturalist Johann Natterer, this medium-sized bat is found throughout Europe. In Jersey, it is the best-documented Myotis species thanks to the Woodland Bat Project, which recorded confirmed breeding in artificial roost boxes.

Ecology & Behaviour

Natterer’s bats roost in tree cavities, bat boxes, and old buildings, emerging late in the evening to forage along woodland edges, hedgerows, and meadows. They are gleaning specialists, capturing beetles, flies, and spiders from surfaces. Their long, broad wings allow for agile, hovering flight.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) and widespread across France, but vulnerable to woodland loss, pesticides, and roost disturbance. In Jersey, bat box monitoring has shown consistent use by Natterer’s bats, reflecting the success of long-term conservation management.

Research Notes

Among European bats, M. nattereri is one of the best-studied in terms of sensory ecology. Classic experiments by Siemers & Schnitzler (2000, 2004) demonstrated its ability to locate prey through passive listening, gleaning insects directly from foliage rather than catching them mid-air. This research overturned the assumption that all bats rely primarily on echolocation for prey detection. Arlettaz et al. (1999–2001) positioned the species within the broader guild of insectivorous bats, identifying it as a “close-to-vegetation” specialist. Rainho & Palmeirim (2011) showed that roost selection depends on proximity to hedgerows and traditional farm buildings, highlighting the value of semi-natural landscapes. In Jersey, long-term data from the Woodland Bat Project (2014–present) confirm breeding within artificial boxes — a significant conservation milestone that demonstrates how habitat management directly benefits a sensitive woodland gleaner.

Fun Fact

Natterer’s bats can use their tail membrane like a scoop, flipping insects into their mouths mid-flight — a behaviour few other bats can perform.

DAUBENTON’S BAT (Myotis daubentonii)

Nicknamed the “water bat,” Daubenton’s bat is closely tied to freshwater habitats. Its graceful, low flight over rivers and reservoirs makes it one of the easiest Myotis bats to observe in Jersey.

Taxonomy & History

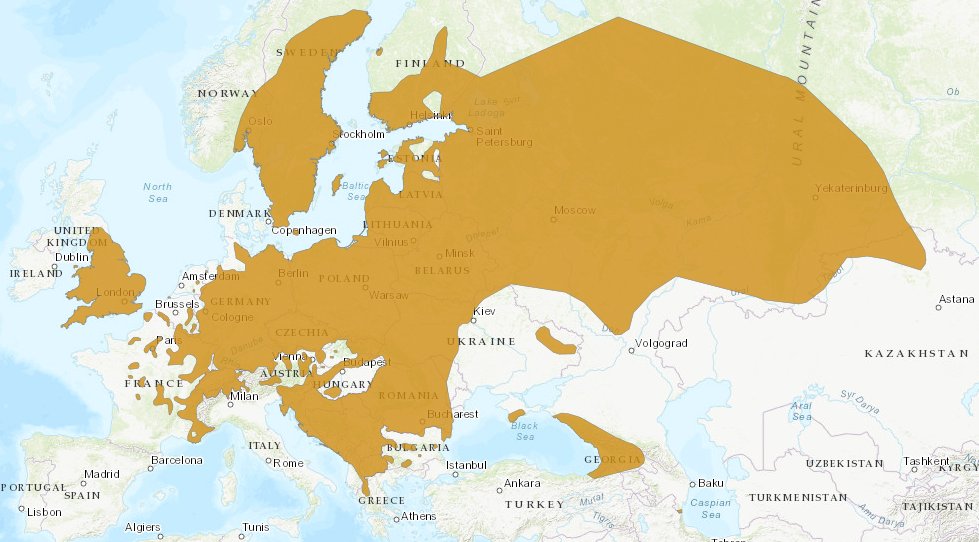

Described in 1759 by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber and named after the French naturalist Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, one of the first scientists to study bats systematically.

Ecology & Behaviour

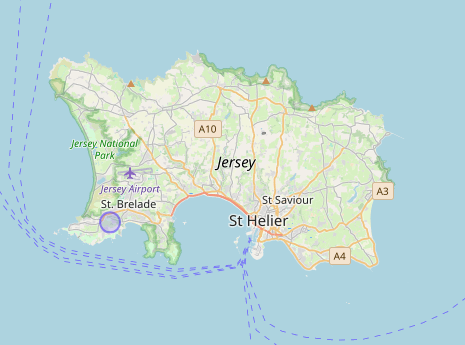

This species forages just centimetres above the surface of still or slow-moving water, scooping insects such as caddisflies and midges with its large feet. It roosts in tree cavities, bridges, and tunnels, and in Jersey it is frequently recorded at reservoirs and along river corridors.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern globally and in France. Its dependence on clean water makes it an excellent bioindicator species — healthy Daubenton’s populations often signal good aquatic insect abundance and water quality. In Jersey, maintaining unlit riparian corridors and water quality is vital for its conservation.

Research Notes

Myotis daubentonii has been at the centre of decades of ecological and biomechanical research. Groundbreaking flight analyses by Jones & Rayner (1988, 1991) showed how its short, broad wings and low wing loading enable slow, stable flight just above water surfaces, perfectly suited for trawling prey. Vaughan, Jones & Harris (1997) linked feeding activity to aquatic insect emergence and demonstrated that the species’ abundance reflects river health. Boonman et al. (1998–2000) refined this by testing how wind and surface ripples affect hunting success, confirming that calm, dark water maximises prey detection. More recent syntheses by Dietz & Kiefer (2016) have consolidated knowledge of its roosting behaviour in bridges and tunnels — human-made habitats that now support large populations across Europe.

Fun Fact

Daubenton’s bats can sometimes be seen “trawling” — dragging their feet or tail membrane along the water’s surface to snatch insects in complete darkness.

GEOFFROY’S BAT (Myotis emarginatus)

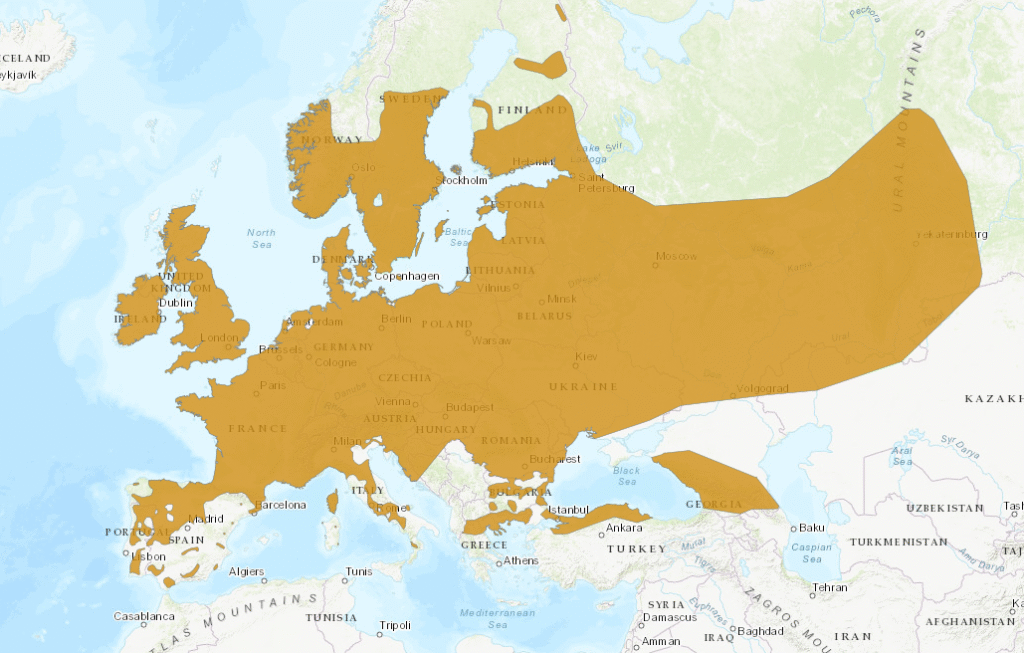

Graceful, warm-toned, and fond of fluttering through farm buildings and woodland edges, the Geoffroy’s bat is one of the most distinctive Myotis species in Europe. With its reddish-brown fur, broad wings, and slow, fluttery flight, it often evokes comparisons to a hovering moth. Although rare in the Channel Islands, occasional acoustic detections and its proximity in northern France suggest that it could occur in Jersey, especially in sheltered valleys and rural outbuildings.

Taxonomy & History

The species was first described by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1806, and later named in his honour. Historically, it was confused with other Myotis bats until detailed morphological analyses clarified its unique identity. It forms part of the “long-winged Myotis” group, which also includes M. myotis and M. blythii.

Ecology & Behaviour

Geoffroy’s bat is primarily a woodland and farmland species, strongly associated with warm, humid environments. It typically roosts in attics, barns, churches, and tree cavities, often forming colonies of up to several hundred individuals. Foraging occurs in woodland glades and around vegetation, where it gleans spiders and small insects directly from surfaces — a feeding style shared with Natterer’s bat. Its slow, buoyant flight and large wing area make it superbly adapted for manoeuvring in tight spaces.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) and Vulnerable in France, Geoffroy’s bat has suffered regional declines due to agricultural intensification and loss of traditional roosts. Across western Europe, populations are increasingly reliant on the conservation of old buildings and roost-friendly renovations. For Jersey, its potential presence highlights the island’s biogeographical link to north-western France, where the species is locally common in Brittany and Normandy.

Research Notes

Geoffroy’s bat has been the focus of extensive ecological research across Europe. Arlettaz (1996) and Arlettaz et al. (1999) provided seminal insights into its foraging strategy, showing that M. emarginatus specialises in gleaning spiders from webs and foliage, often relying on passive listening rather than echolocation. Zahn et al. (2006) examined population genetics and revealed strong philopatry in females, meaning that colonies often remain stable for generations in the same buildings. Recent European telemetry studies (Ancillotto et al., 2014; Uhrin et al., 2018) have shown how Geoffroy’s bats exploit mixed landscapes of woodland and pasture, commuting along hedgerows and rivers. These findings underline the importance of connected habitats — a key conservation focus for regions like Jersey, where small woodland patches and farm complexes provide vital corridors.

Fun Fact

Unlike most bats, Geoffroy’s bat is an avid spider hunter — it often plucks spiders straight from their webs without getting trapped itself, thanks to the fine oil-coated fur on its wings.

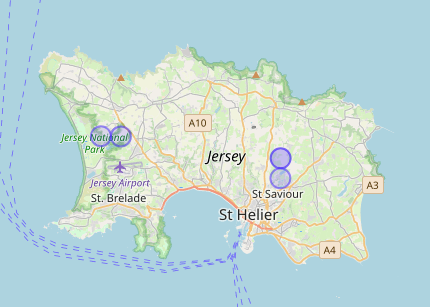

ALCATHOE BAT (Myotis alcathoe)

The Alcathoe bat is one of Europe’s newest and rarest recognised bat species, described only in 2001. It is extremely small, with reddish-brown fur and high-frequency calls. Its presence in Jersey is unconfirmed but possible, based on occasional acoustic detections resembling its signature call pattern.

Taxonomy & History

First described from Greece and Hungary in 2001, M. alcathoe was later confirmed in France, Spain, and the UK (North Yorkshire and Sussex). It is closely related to the whiskered and Brandt’s bats and was likely overlooked for centuries due to their similarity.

Ecology & Behaviour

A forest specialist, it roosts in old trees and forages along wooded streams. Its tiny size (3–5 g) allows it to exploit dense vegetation that other bats avoid. If present in Jersey, it would likely be found in mature, humid woodlands with abundant insect life.

Conservation

Listed as Data Deficient (IUCN) but considered Vulnerable in France. Its rarity and strict habitat needs make it a conservation priority wherever it occurs. Protection of mature forest corridors is essential for any potential Channel Islands populations.

Research Notes

The discovery of Myotis alcathoe reshaped Europe’s understanding of bat diversity. Von Helversen, Heller & Mayer (2001, Acta Chiropterologica) formally described the species from Greece and Hungary, establishing its unique morphology and high-frequency echolocation. Subsequent records by Niermann et al. (2007–2010) confirmed its presence across Central and Western Europe, revealing a far wider range than initially thought. García-Mudarra, Ibáñez & Juste (2009) used mitochondrial and nuclear DNA to clarify its placement within the whiskered-Brandt’s-Alcathoe complex, while the first British confirmations in 2010–2011 (North York Moors and Sussex) demonstrated that it can occur undetected even in well-studied regions. Dietz & Kiefer (2016) later refined acoustic and field identification methods, providing guidance that has since underpinned targeted surveys for this elusive species.

Fun Fact

Myotis alcathoe is named after a tragic figure from Greek mythology: Alcathoe, a princess transformed into a bat by Dionysus.

Further reading

Jones, G. & Rayner, J.M.V. 1988. Flight performance, foraging tactics and echolocation in free-living Daubenton’s bats Myotis daubentonii (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Journal of Zoology, 215, pp. 113-132.

Krueger, F., Harms, I., Fichtner, A., Wolz, I., Sommer, R.S. 2012. High trophic similarity in the sympatric North European trawling bat species Myotis daubentonii and Myotis dasycneme. Acta Chiropterologica, 14(2), pp. 347-356.

Reudi, M & Mayer, F. 2001. Molecular systematics of bats of the Genus Myotis (Vespertilionidae) suggests deterministic ecomorphological convergences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 21(3), pp. 436-448.

Siem, I. et al. 2013. Genome analysis reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the Brandt’s bat Myotis brandtii. Nature Communications, 4, 2212.

Siemers, B.M & Schnitzler, H. 2004. Echolocation signals reflect niche differentiation in five sympatric congeneric bat species. Nature, 429, pp. 657 – 661.

Working to protect and conserve Jersey’s native bat species through research, education, and community involvement.

Join our mailing list to receive updates about bat walks, training, and events.

2025 Jersey Bat Group. All rights reserved.