While pipistrelles and long-eared bats flutter close to hedgerows, a very different class of bat patrols the open skies above Jersey. Larger, faster, and louder, the island’s “big bats” — Leisler’s, Noctule, and Serotine — are true aerial hunters built for speed and endurance. They are the first to appear at dusk, flying high above treetops and fields in pursuit of moths and beetles, often silhouetted against the fading light.

These three species represent the upper end of Jersey’s bat diversity — powerful fliers that bridge local woodlands, farmland, and even offshore airspace. Each tells a story of adaptation, migration, and persistence in a landscape that continues to change.

LEISLER’S BAT (Nyctalus leisleri)

Leisler’s bat is one of Jersey’s most striking species — a medium-sized bat with long, narrow wings and a golden-brown mane of fur around its neck and shoulders. Often the first bat seen on summer evenings, it cuts a distinctive silhouette as it hunts high above open ground, sometimes 30–50 metres up.

Taxonomy & History

First described by Heinrich Kuhl in 1817, Nyctalus leisleri is closely related to the larger Noctule (N. noctula) but occupies a different ecological niche. It was long considered a subspecies of the Noctule until taxonomic revision elevated it to full species status. In the British Isles, Leisler’s bat has an uneven distribution, most abundant in Ireland — where it is the island’s “common big bat” — and increasingly reported in southern England and the Channel Islands.

Ecology & Behaviour

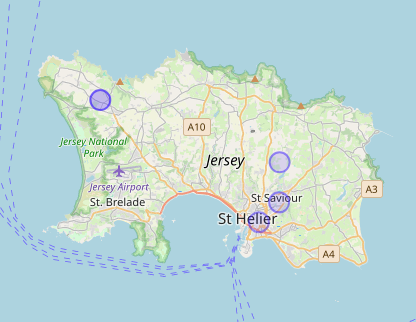

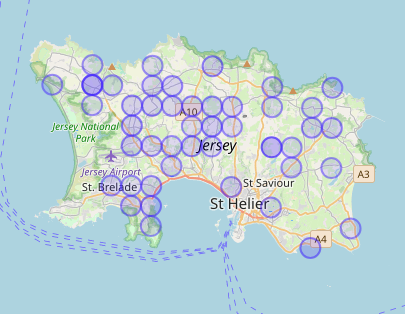

Leisler’s bats prefer open habitats such as parkland, farmland, and woodland edges, where they forage for moths, beetles, and flying ants. Their fast, direct flight and loud echolocation calls allow them to cover large areas efficiently. They roost in tree cavities and occasionally buildings, switching roosts frequently through the summer. In Jersey, acoustic surveys have recorded consistent detections across rural and semi-urban landscapes, suggesting a stable local population and possible breeding.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) and considered Vulnerable in France due to regional declines, Leisler’s bat remains uncommon across most of Europe. In Jersey, it benefits from a mosaic of open countryside and wooded valleys, though continued habitat fragmentation and loss of mature roost trees could threaten its long-term stability.

Research Notes

Leisler’s bat has been widely studied across Europe for its flight ecology and seasonal movements. Waters et al. (1999) demonstrated that its high-altitude flight patterns are linked to insect swarms and weather conditions, while Shiel et al. (1999) in Ireland showed how it adapts to both natural and urban habitats. Rydell and colleagues (2002) explored its energetic efficiency, finding that its wing design maximises flight speed with minimal energy use — traits shared with its larger relative, the Noctule. A comparative analysis by Russo & Jones (2002) revealed that Leisler’s bats emit some of the loudest echolocation calls of any European species, audible to bat detectors over 100 metres away. In recent years, radio-tracking in central Europe (Uhrin et al. 2018) has confirmed that N. leisleri is a partial migrant, with individuals travelling several hundred kilometres between breeding and wintering areas — behaviour that may occasionally bring continental migrants to the Channel Islands.

Fun Fact

Leisler’s bats are sometimes nicknamed the “Lesser Noctule” for their resemblance to N. noctula, but they’re no understudy — they’re one of the few European bats regularly recorded at heights over 100 metres, occasionally detected by aircraft radar.

NOCTULE BAT (Nyctalus noctula)

The Noctule is one of Europe’s largest and most powerful bats, with long, tapered wings and a fast, high flight that makes it more reminiscent of a swift than a typical bat. Although rare in Jersey, it is recorded occasionally during migration periods and may represent transient individuals crossing the Channel.

Taxonomy & History

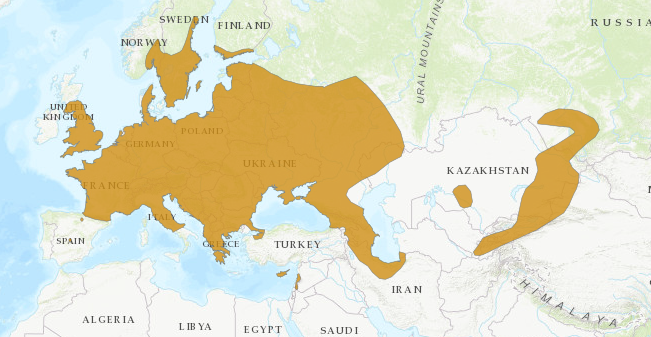

Described by Schreber in 1774, Nyctalus noctula is the type species of its genus and among the best-known of Europe’s “open-air” bats. Its taxonomy is well established, though its migratory ecology continues to reveal surprises: some populations in eastern and central Europe undertake long-distance migrations of over 1,000 km between summer and winter roosts.

Ecology & Behaviour

Noctules roost in hollow trees and sometimes in old buildings, preferring mature deciduous woodlands near open landscapes. They emerge early at dusk — often before full darkness — and hunt high above ground for large insects, especially beetles and moths. Their powerful echolocation calls, around 20–25 kHz, are some of the lowest-frequency bat calls in Europe and can be heard clearly on detectors even at a distance. In the Channel region, occasional records suggest that individuals may cross from mainland France or southern England, exploiting seasonal winds and abundant coastal insects.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) but Vulnerable in France, Noctule populations have declined in many regions due to the loss of ancient trees and roosting cavities. Their reliance on mature woodland makes them sensitive to modern forestry and storm damage. Conservation measures in mainland Europe now include retaining veteran trees and installing “deep-cavity” bat boxes to mimic natural roosts.

Research Notes

Noctules have been the focus of intensive research into bat migration, physiology, and urban ecology. Hutterer et al. (2005) and Popa-Lisseanu et al. (2007) used isotopic and radio-tracking data to show that eastern European populations migrate vast distances, sometimes crossing the Alps and Carpathians. Voigt et al. (2016) investigated their use of tailwinds to reduce energy costs during migration, revealing sophisticated navigation strategies. In western Europe, Vaughan et al. (1997) studied foraging behaviour, confirming the species’ preference for high, open airspace, while Mackie & Racey (2008) documented its increasing adaptation to urban parklands and floodplain forests. For island biogeography, these studies imply that Jersey’s occasional noctule records could represent either exploratory migrants or individuals dispersing from declining populations on the French mainland.

Fun Fact

Noctules are among the fastest bats in the world, capable of speeds exceeding 50 km/h in level flight — faster than a racing pigeon and easily outpacing most aerial insects.

SEROTINE BAT (Eptesicus serotinus)

The Serotine is one of Jersey’s more frequently recorded large bats, a warm-brown, broad-winged species often seen cruising over farmland, pastures, and village streets on warm summer nights. It’s a robust flier that thrives in human landscapes — often roosting in roof spaces, attics, and old stone buildings.

Taxonomy & History

Described by Schreber in 1774, Eptesicus serotinus belongs to a different lineage from Nyctalus, representing the “broad-winged” big bats of Europe. It is closely related to the northern bat (E. nilssonii), though the two occupy distinct climatic zones. Genetic studies have confirmed a single widespread western European species, with subtle regional variation.

Ecology & Behaviour

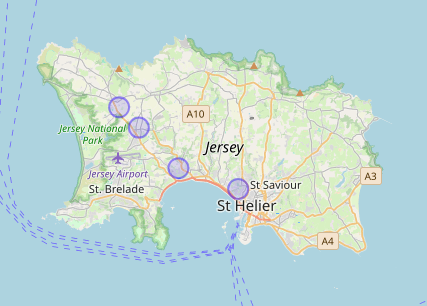

Serotines favour open habitats and roost readily in human structures, particularly older buildings with accessible cavities. They feed on large insects such as beetles, cockchafers, and moths, often hunting along hedgerows and roadsides. Their low-frequency calls (20–25 kHz) make them one of the loudest and most easily detected species on bat recorders. In Jersey, acoustic data from Tahnee Blakemore’s monitoring work and the iBats programme show regular activity across rural parishes, confirming the species as a stable resident.

Conservation

Listed as Least Concern (IUCN) and widespread in France, but dependent on traditional roost sites and rich insect populations. In the Channel Islands, serotines appear well adapted to agricultural and peri-urban habitats, though renovation of older buildings and pesticide use pose ongoing risks.

Research Notes

The Serotine bat has been central to studies of bat foraging ecology and energetics. Rydell (1992) and Vaughan et al. (1997) demonstrated how its broad wings allow efficient slow flight for capturing heavy-bodied insects — particularly scarab and dung beetles. Racey & Swift (1985) examined reproductive physiology, finding that E. serotinus times breeding to match peak insect abundance. More recently, Goerlitz et al. (2010) investigated prey-detection strategies, showing that serotines combine echolocation with passive listening to pinpoint larger prey. Across continental Europe, Arlettaz et al. (2000) and Jones et al. (2011) explored roost selection and population genetics, revealing that colonies show strong fidelity to buildings used for decades. In Jersey, the species’ persistence in both rural and semi-urban environments highlights its adaptability — and its importance as a barometer for agricultural biodiversity.

Fun Fact

Serotines are among the few European bats capable of eating large, hard-shelled beetles — they crunch audibly while feeding in flight, a sound sometimes detectable by nearby listeners on quiet summer nights.

Further reading

Scholz, C., Grabow, M., Reusch, C., Korn, M., Hoffmeister, U. & Voigt, C.C. (2025) Oak woodlands and urban green spaces: Landscape management for a forest-affiliated bat, the Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri). Journal of Environmental Management, 387, 125753.

Ruczyński, I., Nicholls, B., MacLeod, C.D., Racey, P.A. (2010) Selection of roosting habitats by Nyctalus noctula and Nyctalus leisleri in Białowieża Forest – Adaptive response to forest management? Forest Ecology and Management, 259(8), pp. 1633-1641.

Tiede, J., Diepenbruck, M., Gadau, J., Wemheuer, B., Daniel, R., Scherber, C. (2020) Seasonal variation in the diet of the serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus): A high-resolution analysis using DNA metabarcoding. Basic and Applied Ecology, 49, pp. 1-12.

Working to protect and conserve Jersey’s native bat species through research, education, and community involvement.

Join our mailing list to receive updates about bat walks, training, and events.

2025 Jersey Bat Group. All rights reserved.