It is coming up to the end of another year, and with that it is a great time to reflect on some of the new discoveries from 2025!

Earlier in the year we posted about the new research that came out during the first half of 2025:

And now we are ready to round off 2025 by having a look back at all the amazing work our fellow bat researchers and enthusiasts are doing both at home and abroad!

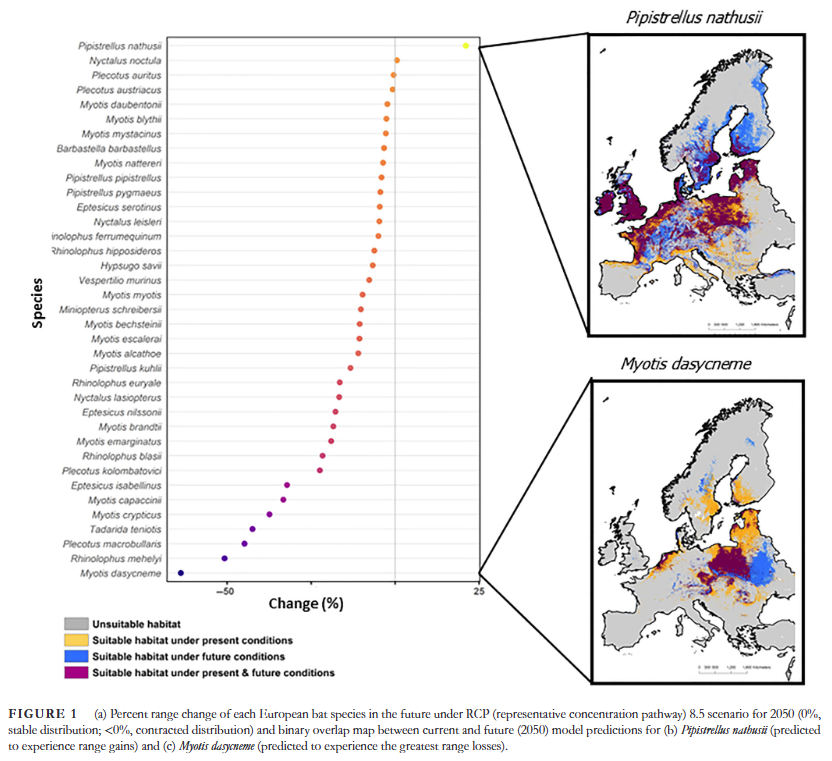

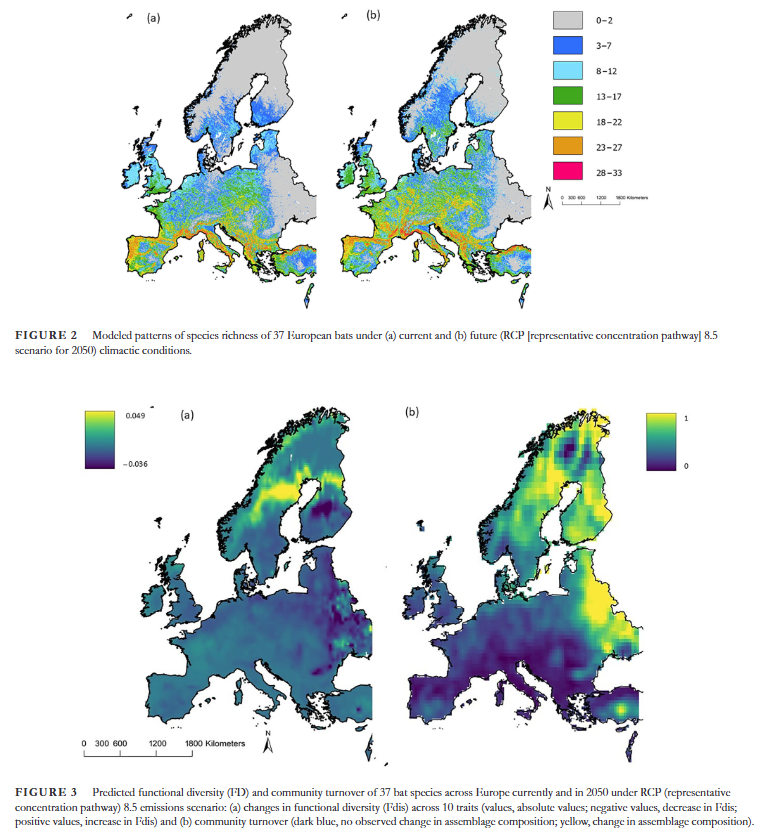

A continental-scale study of 37 European bat species reveals that climate change will drive substantial shifts in species distributions and functional diversity by 2050, with profound implications for ecosystem services across Europe.

Researchers used species distribution models and a comprehensive trait database to predict how climate and land-use changes might affect European bat communities by 2041-2060. The team collected over 14,000 location records from 264 sites across 27 countries through the ClimBats network. They modeled distribution changes under medium (RCP 4.5) and high (RCP 8.5) emission scenarios, then assessed impacts on community composition and functional diversity using 10 key ecological and morphological traits including body mass, diet diversity, wing morphology, and habitat preferences.

Most European bat species (33 of 37) are predicted to experience range contractions, with seven species losing over 30% of their range. Southern Europe faces the greatest losses, while northern latitudes see gains in species richness and functional diversity. However, increased species richness doesn’t always mean improved ecosystem function—some areas gaining species may lose functional diversity as morphologically distinct specialists disappear and are replaced by generalists. Dietary traits showed the most significant changes: Fennoscandia will gain dietary diversity while Eastern Europe, Britain, Italy, and southern Spain face reductions. Mediterranean species like Rhinolophus mehelyi (predicted 50% range loss) and the northern specialist Myotis dasycneme (70% loss) face severe threats, while only Pipistrellus nathusii shows substantial range expansion.

This research fundamentally challenges traditional conservation approaches by revealing that climate change impacts extend beyond simple range shifts to alter the functional roles bats play in ecosystems. Conservation strategies must now incorporate functional diversity metrics, targeting species with key traits predicted to be lost—particularly large-bodied species with diverse diets. Priority areas include southern Spain and Eastern Europe, where functional diversity declines threaten ecosystem resilience and pest control services. The northward shift creates opportunities for proactive conservation, including artificial roost creation in newly suitable areas like Fennoscandia and enhanced landscape connectivity through green corridors. The findings emphasize urgent needs for habitat protection in current ranges, international monitoring networks, and biosecurity measures to prevent additional stressors. Most critically, the work demonstrates that common, widespread species currently classified as “Least Concern” face significant climate-driven threats that warrant immediate attention alongside traditionally prioritized endangered species.

Reference: Fialas, P.C. et al. (2025). Conservation Biology, 39, e70025.

The main author, Penelope Fialas, will be presenting her research on the 11th March 2026 as part of the Winter Talks Series hosted by the Jersey Bat Group. See here for more details:

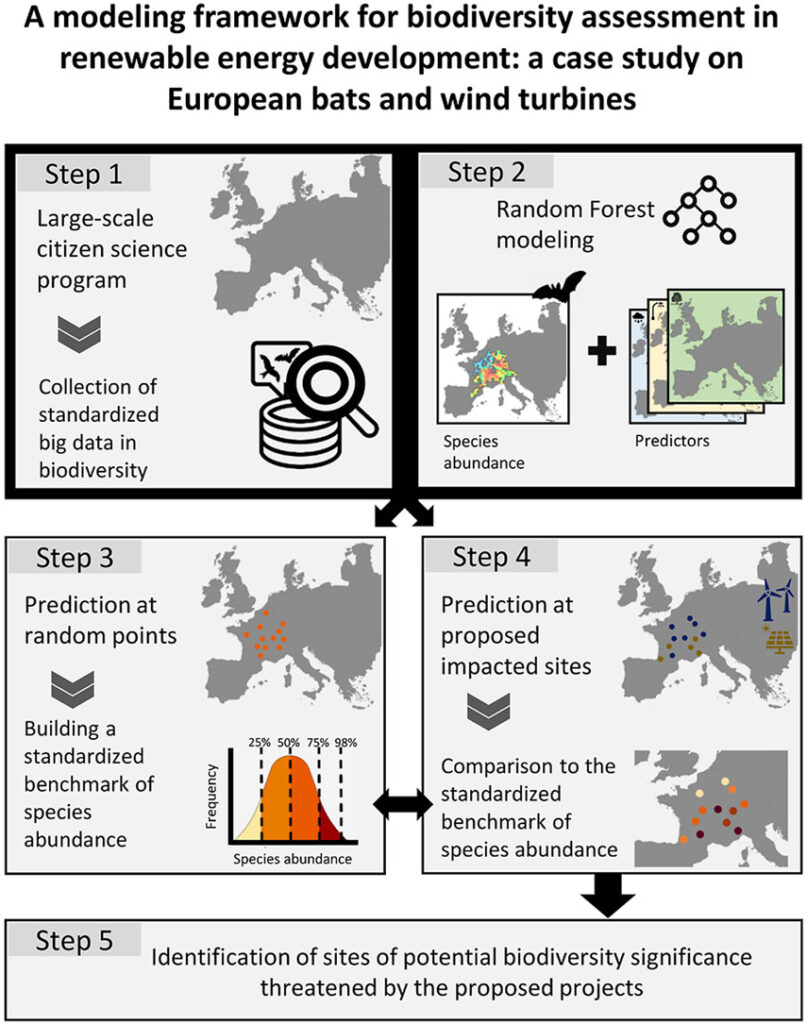

A groundbreaking study published in January 2025 demonstrates how citizen science data can revolutionize wind farm planning to better protect bat populations.

French researchers developed a five-step modeling framework using data from Vigie-Chiro, Europe’s largest standardized bat monitoring program. They analyzed over 1,300 survey sites across two French regions, modeling activity levels for 12 bat species against environmental, climatic, and landscape variables. This created “biodiversity benchmarks” categorizing areas from low to extremely high bat activity. They then tested whether wind turbines approved for construction were appropriately sited in low-activity areas.

The results were alarming: over 90% of approved wind turbines were located in areas of high bat significance. Species with higher collision risks, like noctule bats, were just as likely to be affected as less vulnerable species. Less than 10% of turbines were sited in genuinely low-activity areas for all bat species, suggesting current environmental impact assessments are failing to protect bats despite EU legal protections.

This framework addresses critical weaknesses in current assessments by providing objective, standardized benchmarks based on large-scale data rather than limited site surveys. It enables early identification of high-risk sites before construction, supports evidence-based consultation responses, and helps target mitigation measures like curtailment more effectively. The approach could be extended to other countries with bat monitoring programs and adapted for other renewable energy types. The authors urge policymakers to mandate biodiversity modeling in planning processes, demonstrating that climate action and bat conservation can coexist with better tools.

Reference: Froidevaux et al. (2025). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 211, 115323.

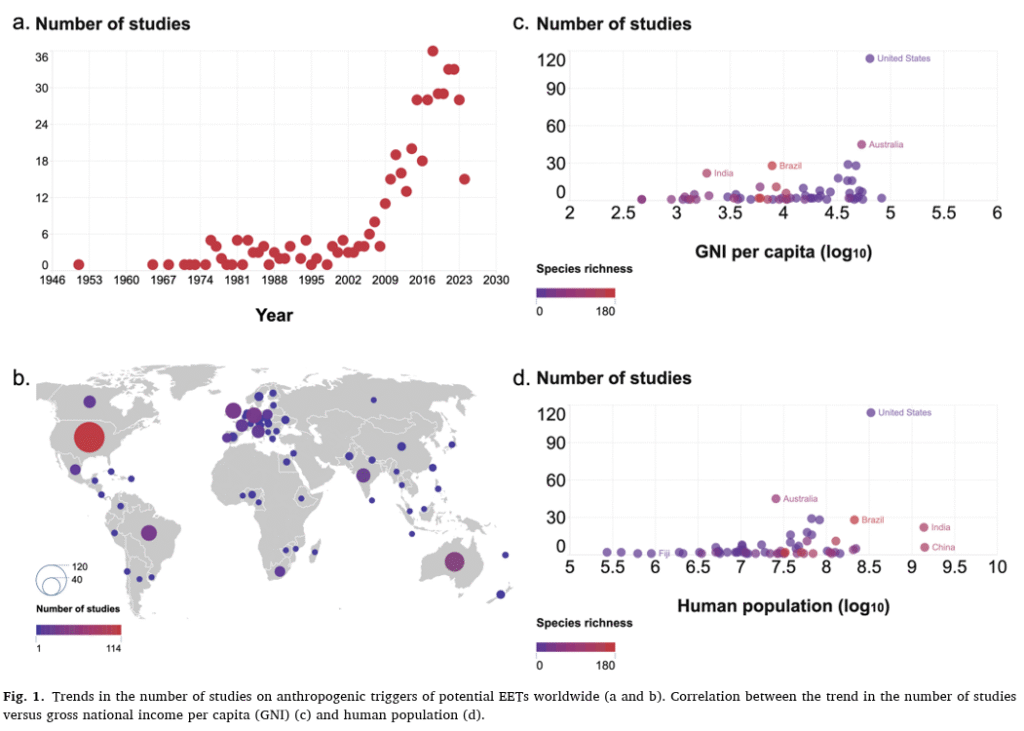

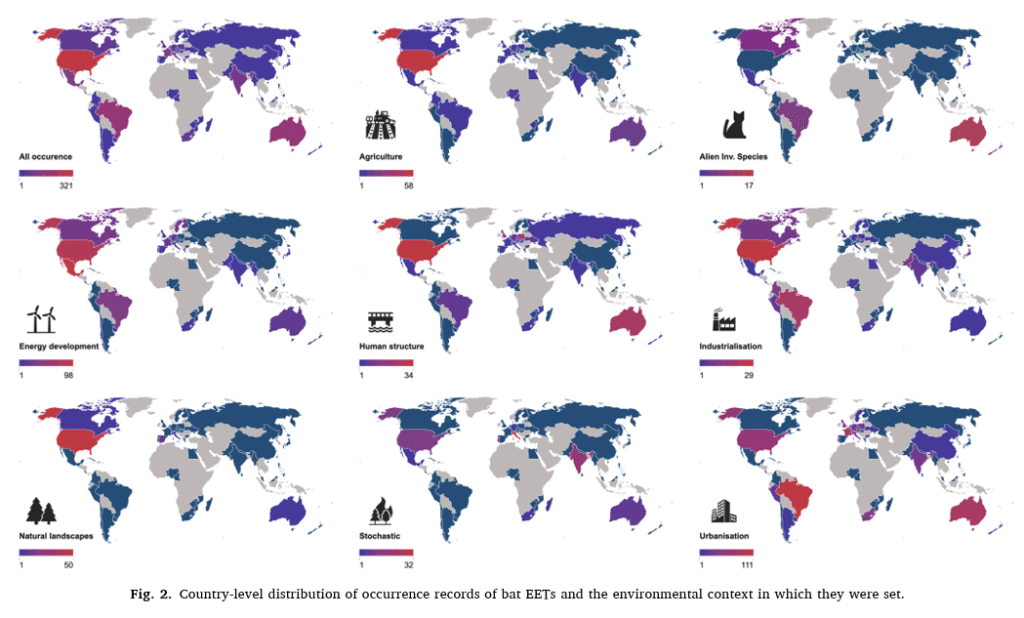

A comprehensive global analysis reveals that 318 bat species face risks from human-created “traps”—habitats that appear suitable but harm survival—with urbanization and energy development as major threats.

Researchers conducted a global review of 486 studies across 64 countries examining ecological and evolutionary traps (EETs) for bats. These traps occur when human-altered environments mislead bats into selecting poor-quality habitats that reduce survival or reproduction. The team analyzed which bat species, ecological traits, and geographic regions were most vulnerable. They examined eight environmental contexts including urbanization, energy development, agriculture, and industrialization, documenting trap mechanisms (attraction vs. degradation) and consequences for bat populations. Using statistical models, they identified biological traits that predict susceptibility to traps.

The analysis identified 318 bat species at risk from anthropogenic traps, with urbanization affecting 66% of at-risk species, followed by energy development (37%) and agriculture (25%). Wind turbines, roads, and artificial lighting were dominant trap triggers. Smaller-bodied, insectivorous species with wide geographical ranges and low habitat specialization were most vulnerable. Surprisingly, widespread generalist species faced higher risks than specialists, contrary to predictions. Colonial species forming large aggregations were particularly susceptible. Most affected species (79%) were classified as Least Concern, suggesting current conservation priorities may overlook significant trap-related threats.

This research highlights a critical gap: conservation efforts may inadvertently focus on areas with high bat densities that are actually ecological traps, undermining recovery efforts. The findings challenge conventional approaches by showing that even common, adaptable species face serious threats from human-altered environments. The study emphasizes that managing trap risks requires understanding species-specific responses beyond traditional threat assessments. Urban light pollution, artificial roosts, and energy infrastructure create complex scenarios where bats are lured to seemingly favorable but ultimately deadly habitats. Conservation strategies must extend beyond protecting threatened species to include trap mitigation for widespread bats whose population declines may be silent but significant.

Reference: Tanalgo et al. (2025). Biological Conservation, 305, 111110.

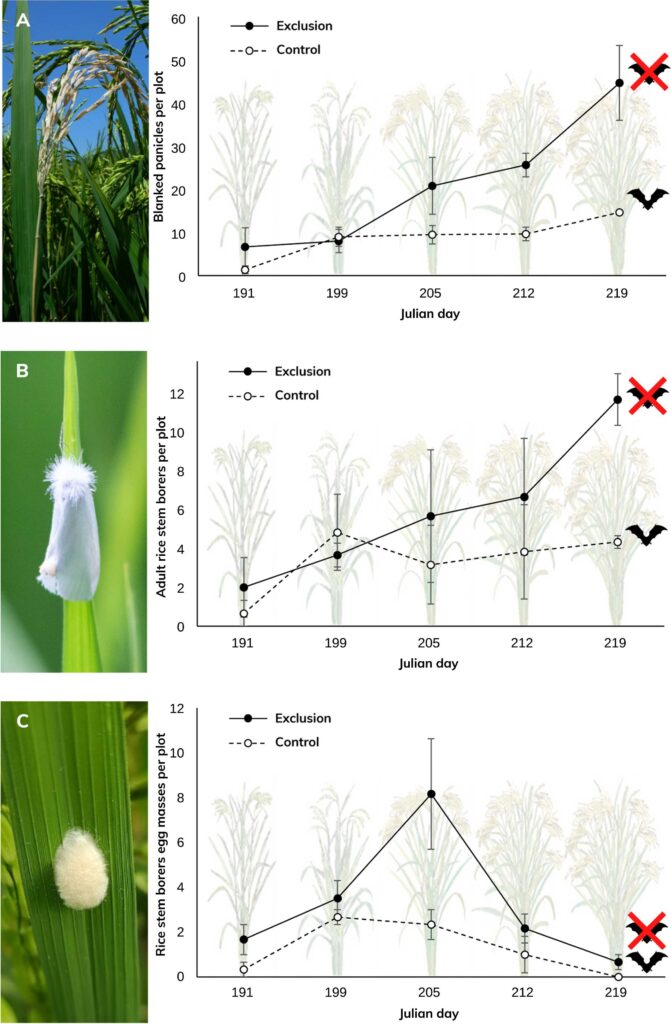

Researchers used large field exclosures in Mexico to directly measure how insectivorous bats reduce rice stem borer damage, finding a 58% reduction in crop damage worth up to $606.90 per hectare annually.

Scientists conducted nocturnal exclusion experiments across six rice fields in Morelos State, Mexico during the 2021 growing season. They built six large exclosures (20m × 20m × 5m high) with nets that excluded bats at night but allowed daytime insect predators like birds. Researchers counted rice stem borers (nocturnal moths whose larvae damage rice), egg masses, adult moths, and damaged panicles every six days from flowering to harvest. They also used acoustic recorders to monitor bat activity and identified 12 bat species/groups from four families. Economic values were calculated for both unmilled and milled rice, then extrapolated to state and national levels under low, medium, and high pest infestation scenarios.

Bat presence reduced crop damage by 58%, with plots exposed to bats showing 2.2 times fewer damaged panicles than exclusion plots. Adult rice stem borers were 1.6 times more abundant and egg masses 2.4 times more abundant where bats were excluded. The most active species was Balantiopteryx plicata (35% of bat activity), followed by vespertilionid bats. While direct weight yield differences weren’t statistically significant due to low pest levels, damage-based calculations estimated values of $3.39–8.03 per hectare for the study year, potentially reaching $256.42–606.90 per hectare under high infestation scenarios. National projections suggest bats could prevent losses affecting 17,000 to over 1.3 million people’s annual rice consumption.

This study provides the first direct experimental evidence of bats suppressing rice pests in the Americas, demonstrating their value beyond theoretical estimates. The findings support integrating bat conservation into integrated pest management strategies for rice—a staple crop feeding over half the world’s population. The research highlights that even common, generalist bat species provide significant economic benefits to agriculture, suggesting conservation incentives like biodiversity-friendly certifications could help protect both bat populations and food security. Results are particularly relevant for Mexico’s “Morelos rice” Denomination of Origin, where maintaining bat populations could help sustain this culturally and economically important crop facing threats from urbanization.

Reference: Sierra-Durán et al. (2025). Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 383, 109503.

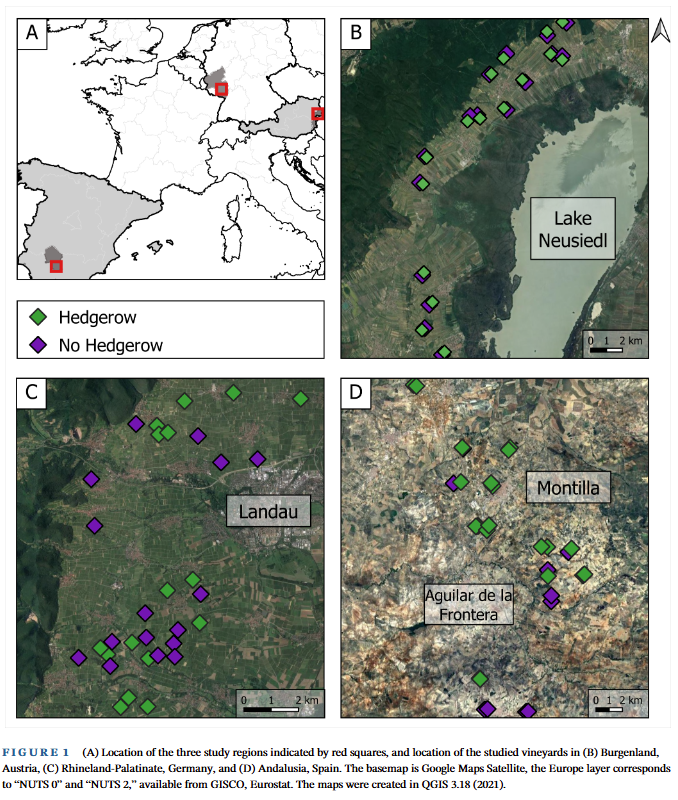

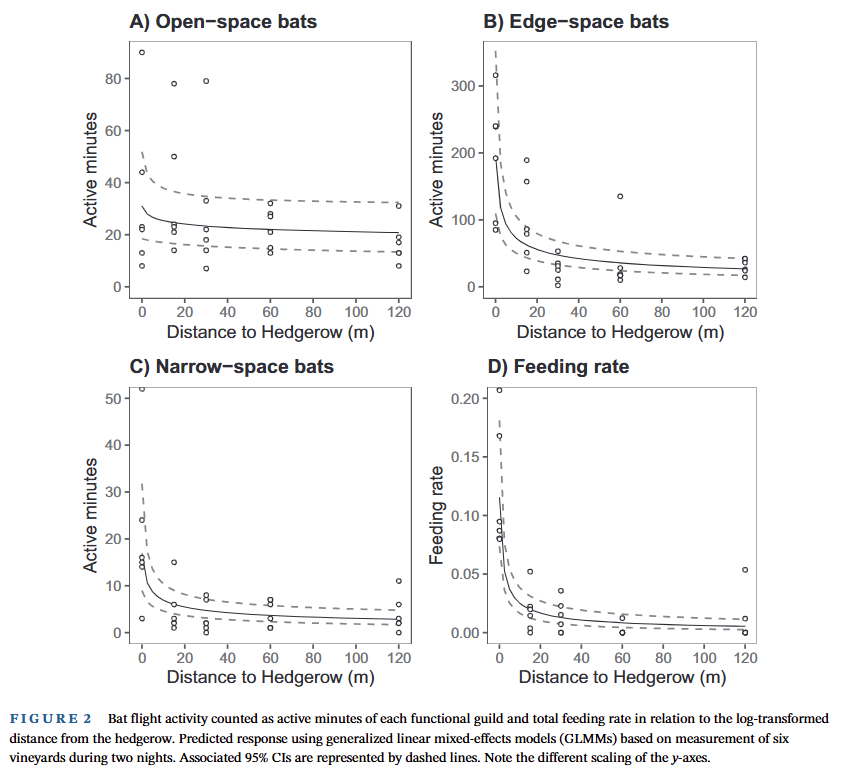

Researchers monitored bat activity across 94 vineyards in Austria, Germany, and Spain using acoustic recorders, demonstrating that hedgerows dramatically enhance bat activity and feeding rates across all three regions, with effects strongest for edge-space foraging bats.

Scientists conducted passive acoustic monitoring over four nights in vineyards across three European wine-growing regions: Rhineland-Palatinate (Germany), Burgenland (Austria), and Andalusia (Spain). In total, 94 vineyards were studied—42 with adjacent hedgerows and 52 without. Bats were classified into functional guilds based on foraging habitat preferences: open-space foragers (adapted to open air hunting), edge-space foragers (adapted to foraging along vegetation), and narrow-space foragers (hunt within vegetation). In Germany, researchers also conducted transect studies in six vineyards, placing acoustic recorders at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120m from hedgerows to measure how bat activity declined with distance. Landscape composition within 150m buffers was characterized, including woody areas, vineyard cover, and distances to forests and built-up areas.

Bat activity decreased dramatically with distance from hedgerows in a guild-specific manner. Open-space bats decreased activity by 50% at 120m from hedgerows, while edge- and narrow-space bats declined by over 80%. Feeding rate dropped 90% between the hedgerow edge and 120m into vineyards. Comparing vineyards with and without hedgerows, edge-space bats (dominated by Pipistrellus species) showed 2–5 times higher activity in vineyards with hedgerows across all countries, with the strongest effects in Germany (4×) and Spain (5×). Open-space bats only showed significant hedgerow response in Spain (5× higher), likely because Spain had lowest woody cover (1.2%) and greatest forest distances (19,745m). Narrow-space bats responded positively only in Austria (1.7× higher). Feeding rates were 1.3–4 times higher in vineyards with hedgerows. Surrounding landscape influenced responses: in Germany, open-space bats avoided vineyards with >80% vineyard cover; narrow-space bats preferred proximity to forests; edge-space bats in Austria were positively related to vineyard proportion and forest distance.

This study provides the first comprehensive multi-country evidence that hedgerows are critical habitat features for bats in permanent crop landscapes, with effects equal to or stronger than those documented in arable fields. The findings are particularly relevant given that European Union Common Agricultural Policy requires maintenance of non-productive areas like hedgerows for arable crops but not for permanent crops like vineyards. Results suggest this policy gap should be addressed, as hedgerows provide essential foraging habitat, prey abundance, protection from predators, and acoustic orientation cues—especially important given bats’ potential role as natural predators of Lobesia botrana, a major vineyard pest. The consistency of hedgerow benefits across three climatically and geographically distinct regions (Mediterranean Spain, continental Germany, and transitional Austria) despite different bat communities and landscape contexts demonstrates the robust value of hedgerow conservation. By supporting bats that can consume two-thirds of their body mass nightly in insects including lepidopteran pests, hedgerow conservation and restoration could enhance natural pest control while simultaneously benefiting other taxa including bees and birds that also depend on these landscape features.

Reference: Chávez et al. (2025). Ecosphere, 16(1), e70143.

A groundbreaking study reveals that white-nose disease—one of the most devastating wildlife diseases in history—is caused not by a single pathogen but by two distinct cryptic fungal species with different host preferences, fundamentally changing our understanding of this bat disease.

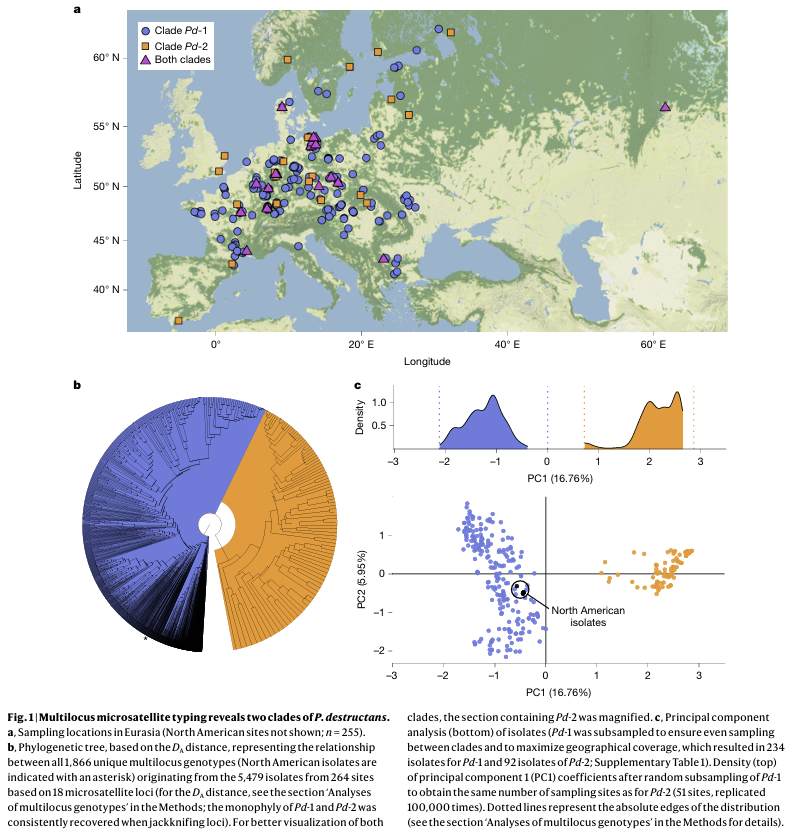

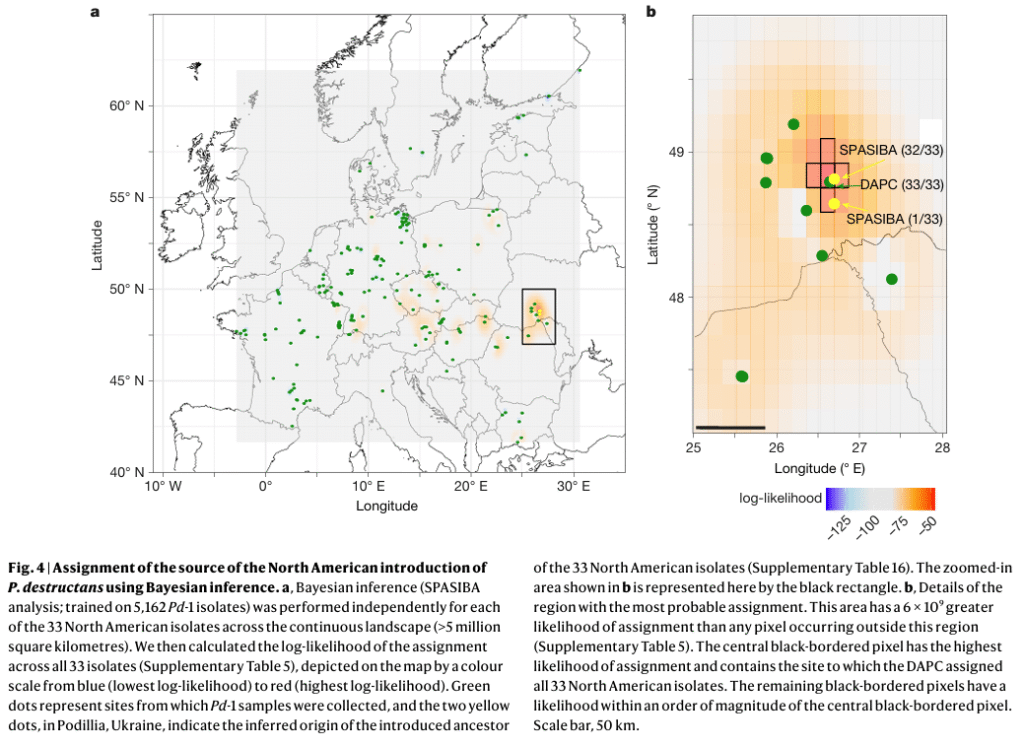

Researchers analyzed an extensive collection of 5,479 fungal isolates from 264 sites across 27 countries spanning Europe, Asia, and North America. Using multilocus microsatellite genotyping and whole-genome sequencing, they investigated the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The team integrated molecular data with field-based ecological observations, including host species identity, environmental conditions (temperature and humidity), and disease manifestations. Through phylogenetic analyses, population genetics, and demographic modeling, they examined genome organization, recombination patterns, and geographic structure to trace the pathogen’s diversity and dispersal history.

The analysis revealed two sympatric cryptic species: Pd-1 (P. destructans sensu stricto) and Pd-2. Each exhibits strong host specialization—87% of Pd-1 infections occurred on Myotis myotis/blythii bats, while M. daubentonii showed near-certain infection with Pd-2 exclusively. Both species demonstrated widespread recombination within clades but strict reproductive isolation between them, with inter-clade genetic divergence exceeding 1.6% across genomes. Surprisingly, Pd-1 dominates European populations (95% of samples), while preliminary evidence suggests Pd-2 may dominate East Asia. The North American introduction was definitively traced to Podillia, Ukraine—a region with extensive cave systems and significant international caving activity—pinpointing the source within a 9-kilometer radius.

This discovery has profound implications for managing white-nose disease globally. The existence of a second pathogenic species with different host preferences creates new risks: bat populations recovering from Pd-1 exposure could face renewed threats if Pd-2 is introduced to their regions. Currently absent from North America, Pd-2’s introduction could devastate species previously unaffected by Pd-1, repeating the catastrophic mass mortality events. The findings emphasize that pathogen variability—not just host traits or environmental conditions—must be integrated into disease surveillance and management strategies. The precise identification of the Ukrainian source region highlights the critical role of human-mediated dispersal through international caving activities, underscoring urgent needs for improved biosecurity protocols and equipment decontamination practices. Conservation efforts must now account for multiple cryptic pathogens rather than treating white-nose disease as a single-pathogen system, requiring species-specific risk assessments and prevention strategies to prevent further spread beyond native ranges.

Reference: Fischer, N.M. et al. (2025). Nature, 642, 1034–1040.

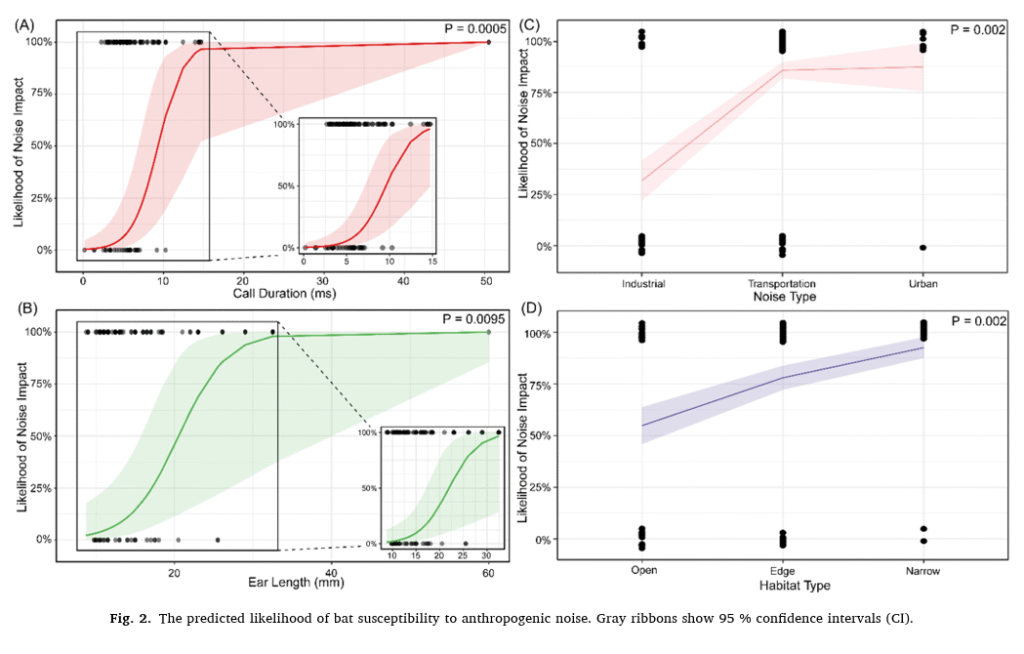

A global meta-analysis of 60 bat species reveals that habitat preference is the primary ecological trait explaining differential sensitivity to anthropogenic noise, with bats foraging in forests and vegetated areas significantly more vulnerable than open-space foragers.

Researchers conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis examining anthropogenic noise effects on bats globally. They surveyed 33 peer-reviewed studies covering 60 bat species (approximately 4% of all bat species) from 33 studies across all continents except Antarctica. The analysis employed generalized linear models and phylogenetically controlled random forest models to identify biological and ecological traits predicting noise sensitivity. Key variables examined included echolocation call parameters (duration, peak frequency, end frequency), morphological characteristics (body size, forearm length, ear length), foraging habitat type (open, edge, narrow spaces), foraging mode (active echolocation vs. passive listening), and behavioral context (foraging, orientation, vocalizing). The meta-analysis comprised 56 effect sizes from 12 experimental studies on 17 species, with Hedges’ g calculated to standardize response variables across different measurement scales.

Bat species foraging in narrow and edge spaces showed significantly greater sensitivity to anthropogenic noise than open-space foragers, with habitat type explaining 25.97% of response variation. Transportation and urban noise proved more disturbing than industrial noise (explaining 30.25% of variation), likely due to their temporal and spectral fluctuations that prevent habituation. Bats producing longer echolocation calls exhibited increased vulnerability (explaining 26.85% of variation), particularly horseshoe bats and leaf-nosed bats using constant-frequency calls for hunting near vegetation. Species with larger ears relative to body size and smaller overall body sizes showed heightened sensitivity (explaining 13.04% and 3.89% of variation respectively). Foraging bats were more sensitive to noise disturbance than those engaged in orientation or vocalizing activities. Notably, only 92% of studied species belonged to families Vespertilionidae and Molossidae, with research heavily concentrated in Europe (30.3%) and North America (27.3%), while Africa accounted for just one study.

This research fundamentally shifts conservation strategy from species-specific approaches to trait-based management focused on habitat characteristics. The findings provide direct, actionable guidance for infrastructure planning: roads and development near forests require careful noise management, as vegetation-dependent bats face disproportionate impacts. This vulnerability is particularly concerning given that forests serve as critical roosting and foraging grounds for many species, yet have experienced severe losses over 30 years, especially in tropical and subtropical regions that harbor the greatest bat diversity. Conservation priorities should focus on protecting foraging habitats in vegetated areas, not just roost sites, as foraging bats show heightened noise sensitivity. The study recommends enhanced noise mitigation for transportation corridors near forests, careful management of recreational noise in wooded areas, and recognition that forest loss combined with noise pollution creates compounding threats. The meta-analytical approach demonstrates how trait-based frameworks can resolve seemingly conflicting individual case studies, offering scalable conservation solutions applicable across species and regions without requiring exhaustive species-by-species experimentation.

Reference: Li, A. et al. (2025). Biological Conservation, 302, 110974.

As 2025 draws to a close, it has been another remarkable year for bat research—one that has deepened understanding of the complex challenges facing bat populations worldwide while reinforcing the critical importance of evidence-based conservation action.

The research highlighted here paints a sobering picture of the pressures bats face in a rapidly changing world. Climate change is reshaping where bats can survive, with Mediterranean species facing dramatic range contractions while ecosystems struggle to maintain functional diversity even as some gain species richness. Anthropogenic development continues to fragment and degrade critical habitats—from poorly sited wind turbines that disregard bat activity hotspots, to urban expansion and agricultural intensification that create ecological traps for hundreds of species. Noise pollution from traffic and urban activity disrupts the acoustic landscape that forest bats depend upon for survival. And emerging diseases like white-nose syndrome, now revealed to be caused by two distinct cryptic fungal species, threaten populations still recovering from previous outbreaks.

Yet amid these challenges, this year’s research also illuminates pathways forward. Scientists have demonstrated that hedgerows can amplify bat activity and pest suppression services in agricultural landscapes by up to five-fold. Researchers have quantified the substantial economic value bats provide to rice farmers, translating ecological function into tangible human benefit. Studies have identified that habitat preference—rather than dozens of complex biological traits—can guide landscape-scale noise mitigation strategies. Evidence has shown that trait-based conservation frameworks can protect multiple vulnerable species simultaneously, making efficient use of limited resources.

What emerges from these seven studies is a clear message: conservation work matters. Every hedgerow planted, every wind turbine carefully sited, every forest corridor protected, every noise barrier installed contributes to safeguarding bat populations and the irreplaceable ecosystem services they provide. The researchers, conservation practitioners, land managers, and policymakers advancing this work are building the foundation for bat conservation in an uncertain future.

Bats have persisted for over 50 million years, surviving ice ages, continental shifts, and dramatic environmental changes. With continued dedication to understanding their needs and translating that knowledge into action, these extraordinary animals can continue to navigate the night skies—as insect suppressors, seed dispersers, pollinators, and sentinels of ecosystem health—for millions of years to come.

The challenges are substantial, but so too is the collective capacity to address them. As 2026 approaches, the knowledge gained this year, the commitment to evidence-based conservation, and the recognition that every contribution—whether a groundbreaking study or a single hedgerow—helps secure a future for bats and the ecosystems they support.

Working to protect and conserve Jersey’s native bat species through research, education, and community involvement.

Join our mailing list to receive updates about bat walks, training, and events.

2025 Jersey Bat Group. All rights reserved.