If you’ve ever taken a summer stroll at dusk in the Channel Islands, the tiny, darting shapes you’ve seen flitting overhead were almost certainly pipistrelles. These small bats are the most familiar and widespread members of our bat community, often weaving through gardens, farmland edges, and even around streetlights. Despite their size — many weigh no more than a pound coin — they are ecological heavyweights, eating thousands of insects each night and playing an important role in keeping insect numbers in check.

For a long time, people thought “the pipistrelle” was just one species. In fact, science has revealed a far richer story. Jersey is home to four different pipistrelles: the common pipistrelle, the soprano pipistrelle, the Kuhl’s pipistrelle, and the Nathusius’s pipistrelle. Each looks much the same to the naked eye, but their voices, behaviours, and lifestyles are surprisingly different. Some are abundant residents, some are wetland specialists, one is a Mediterranean coloniser moving north, and another is a long-distance migrant crossing seas.

So, while they may all look like “little brown bats,” the pipistrelles of Jersey reveal a fascinating spectrum of ecology, adaptation, and discovery. Let’s meet them!

COMMON PIPISTRELLE (Pipistrellus pipistrellus)

The common pipistrelle is by far the most frequently seen bat in Jersey, and across much of Europe. If you’ve spotted a bat fluttering over your garden at dusk, it was almost certainly this species. Small — weighing just 4–8 grams, about the same as a £1 coin — it is an ecological powerhouse. A single individual can consume up to 3,000 midges in a single night, making pipistrelles an important natural control for insect populations.

Taxonomy & History

The species was first described by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in 1774. For centuries, pipistrelles were treated as a single species, until advances in bioacoustics and genetics revealed that there were actually two: the common pipistrelle (P. pipistrellus), echolocating at ~45 kHz, and the soprano pipistrelle (P. pygmaeus), calling at ~55 kHz. This taxonomic split was formally recognised in 1999 following work by Gareth Jones and colleagues at the University of Bristol.

Ecology & Behaviour

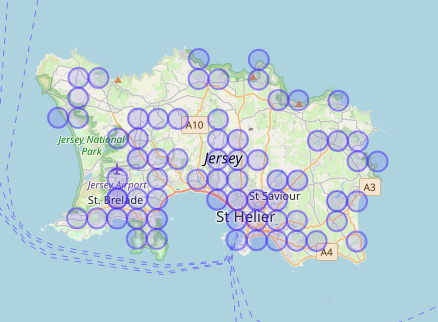

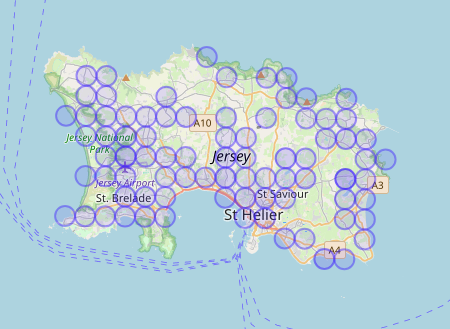

Common pipistrelles are adaptable and opportunistic. They roost in buildings, trees, and bat boxes, emerging at dusk to hunt swarms of small flies and midges along hedgerows, woodland edges, and over water. Their fast, zig-zagging flight makes them highly manoeuvrable, able to exploit a wide range of habitats. In Jersey, they are frequently recorded in gardens, agricultural landscapes, and coastal margins.

Conservation

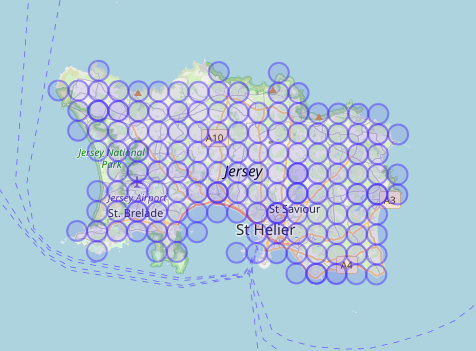

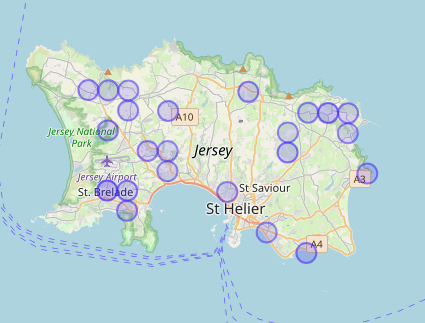

Globally, the common pipistrelle is listed as Least Concern (IUCN), and is considered “common” in France (Mammifères de Bretagne). In Jersey, its abundance makes it an excellent indicator of wider environmental change. While resilient, it is not immune to threats: modern building renovations can remove roosts, and increasing light pollution can disrupt commuting routes and foraging. Long-term monitoring projects such as iBats and JBatS rely heavily on pipistrelle detections to build population trends.

Research Notes

Because of its abundance and adaptability, the common pipistrelle has become one of the most studied bat species in Europe. Research by Gareth Jones (Bristol) and the late Kate Barlow (Bat Conservation Trust) has highlighted its roost ecology, echolocation, and role as an urban survivor. Locally, pipistrelles are at the centre of acoustic monitoring projects across Jersey, making them the “baseline bat” for understanding how our wider bat community is changing.

Fun Fact

Despite their small size, common pipistrelles can live surprisingly long lives: the record is over 16 years for a wild individual in Europe.

SOPRANO PIPISTRELLE (Pipistrellus pygmaeus)

The soprano pipistrelle is a close relative of the common pipistrelle, and the two look almost identical to the naked eye. What sets them apart is their voice: soprano pipistrelles echolocate at a higher frequency, around 55 kHz compared to the common pipistrelle’s 45 kHz. In the Channel Islands, this makes the soprano pipistrelle a specialist of wetland and riparian habitats, where its high-pitched calls are ideal for detecting small insects clustering near water.

Taxonomy & History

For most of history, the soprano pipistrelle was not recognised as a separate species. Both were lumped under Pipistrellus pipistrellus until the 1990s, when acoustic surveys revealed distinct call frequencies. Genetic and morphological analyses confirmed this split, and in 1999 the soprano pipistrelle (P. pygmaeus) was formally described as a distinct species by Professor Gareth Jones and colleagues. This taxonomic breakthrough reshaped pipistrelle research, showing that two widespread species had been hiding in plain sight all along.

Ecology & Behaviour

Soprano pipistrelles are particularly associated with lakes, rivers, reservoirs, and wetlands, where they hunt aquatic midges, caddisflies, and other small insects. They roost in buildings, bat boxes, and tree holes, often forming maternity colonies of 50–200 individuals. Flight is fast and fluttery, with bats weaving close to vegetation or skimming low over water. In Jersey, they are less abundant than common pipistrelles but still regularly recorded in surveys, especially in areas with open freshwater.

Conservation

The species is listed as Least Concern globally (IUCN) and “common” in France. However, soprano pipistrelles are highly dependent on healthy wetland systems, making them sensitive to water pollution, drainage, and disturbance. Light pollution around rivers and reservoirs can also alter insect availability and bat activity. Protecting wetland habitats in Jersey is therefore key to supporting local soprano pipistrelle populations.

Research Notes

The discovery of the soprano pipistrelle as a separate species has been a landmark in bat research, showing how bioacoustics can revolutionise taxonomy. Ongoing studies across Europe track its roosting behaviour and maternity colony dynamics, while in the UK it has become a flagship species for wetland conservation. In the Channel Islands, soprano pipistrelles are a regular presence in acoustic surveys, though less numerous than their common cousins.

Fun Fact

In Ireland, soprano pipistrelles are the most common bat species — so much so that they were chosen as a national symbol during the Irish Millennium celebrations in 2000.

KUHL’S PIPISTRELLE (Pipistrellus kuhlii)

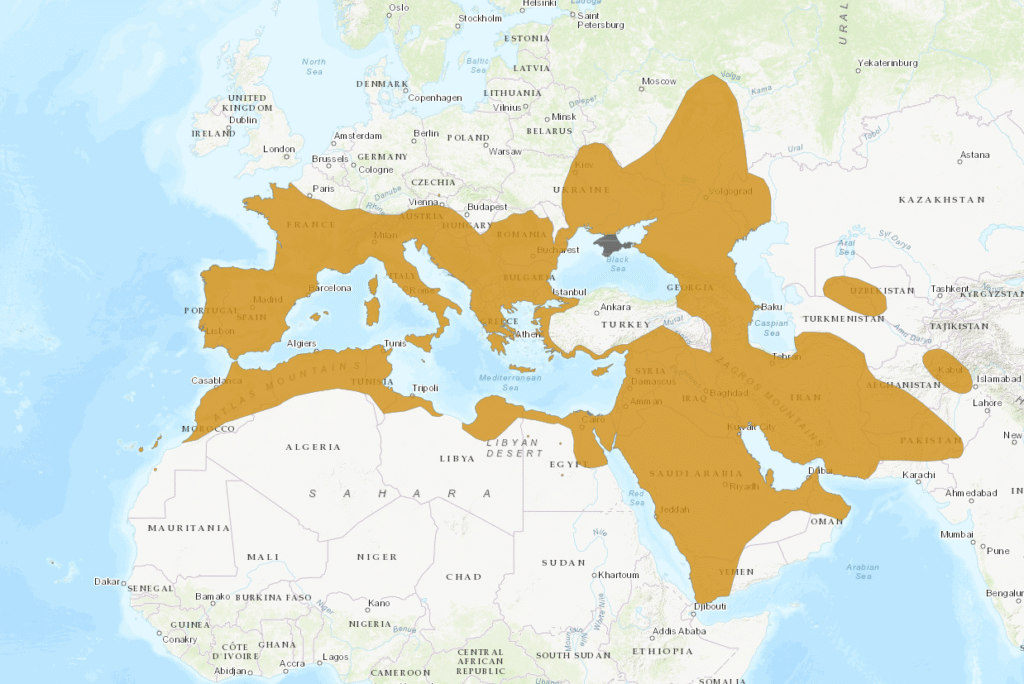

Kuhl’s pipistrelle is one of Jersey’s most distinctive bats, not because of how it looks — it is very similar to other pipistrelles — but because of where it comes from. Originally a Mediterranean bat, it has expanded northwards over the past few decades and is now a regular resident in Jersey. Its presence makes the island one of the few places in the British Isles where this species is encountered, highlighting Jersey’s role as a crossroads between continental and northern European bat faunas.

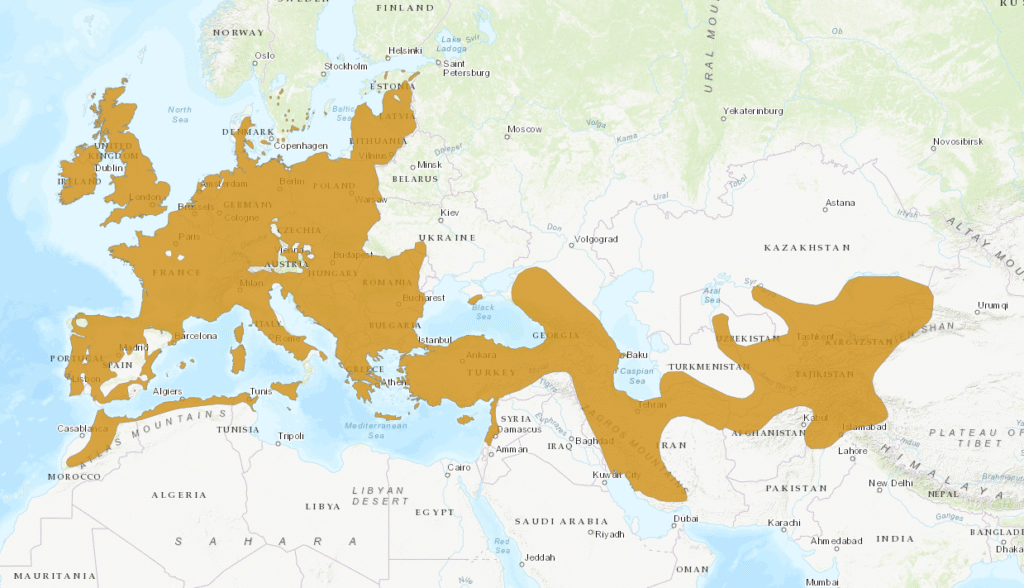

Taxonomy & History

The species was first described in 1817 by the German zoologist Heinrich Kuhl, after whom it is named. Long considered a “southern bat,” P. kuhlii has undergone a rapid range expansion since the late 20th century, linked to warmer climates and urban development. In Britain, confirmed records are still exceptional, making Jersey’s population an important outpost of this expanding species.

Ecology & Behaviour

Kuhl’s pipistrelle often roosts in buildings, including modern structures, attics, and crevices in walls. It emerges soon after sunset to hunt moths, beetles, and small flies in open habitats. Unlike common and soprano pipistrelles, Kuhl’s is strongly associated with urban and suburban landscapes, where streetlighting attracts insect prey. Acoustic surveys in Jersey regularly detect it in built-up areas and along the southern coast.

Conservation

Globally, the species is assessed as Least Concern (IUCN), and in mainland France it is considered to be expanding. In Jersey, it appears to be establishing itself as a stable resident, though precise population numbers remain unknown. The main conservation concern is light pollution, which benefits Kuhl’s pipistrelle in the short term but can disadvantage other species and disrupt wider ecosystems. Monitoring its spread provides valuable insights into how bats respond to urbanisation and climate change.

Research Notes

Kuhl’s pipistrelle has been the focus of several European studies on urban bat ecology. Research in Italy, Spain, and France has shown how well it adapts to cities, often roosting in apartment blocks and feeding around streetlamps. Its presence in Jersey has been confirmed through multiple acoustic surveys, including iBats and JBatS, as well as targeted studies by local researchers.

Fun Fact

Because it thrives in urban environments, Kuhl’s pipistrelle is sometimes nicknamed the “city bat” of southern Europe. In parts of Italy, it is one of the few bat species commonly seen flying among high-rise apartment buildings.

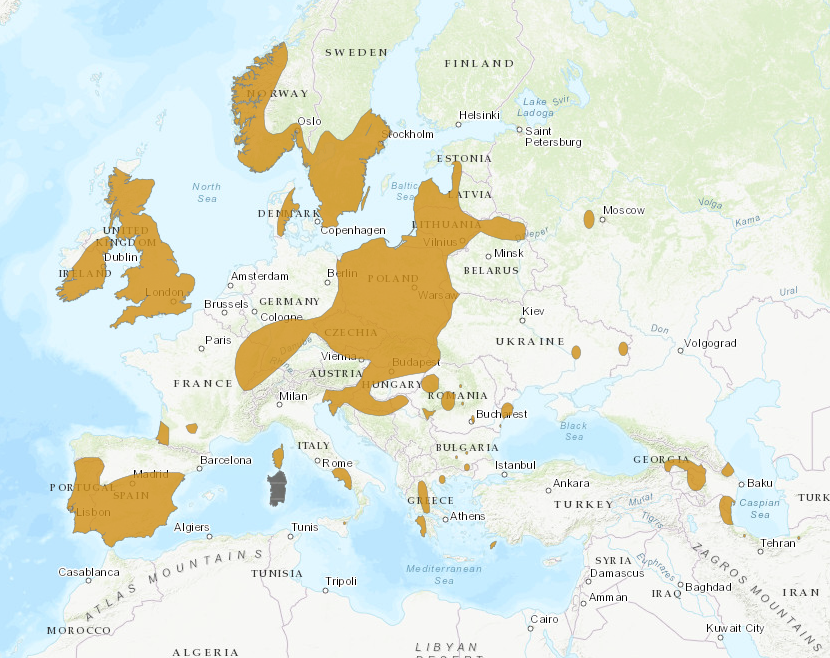

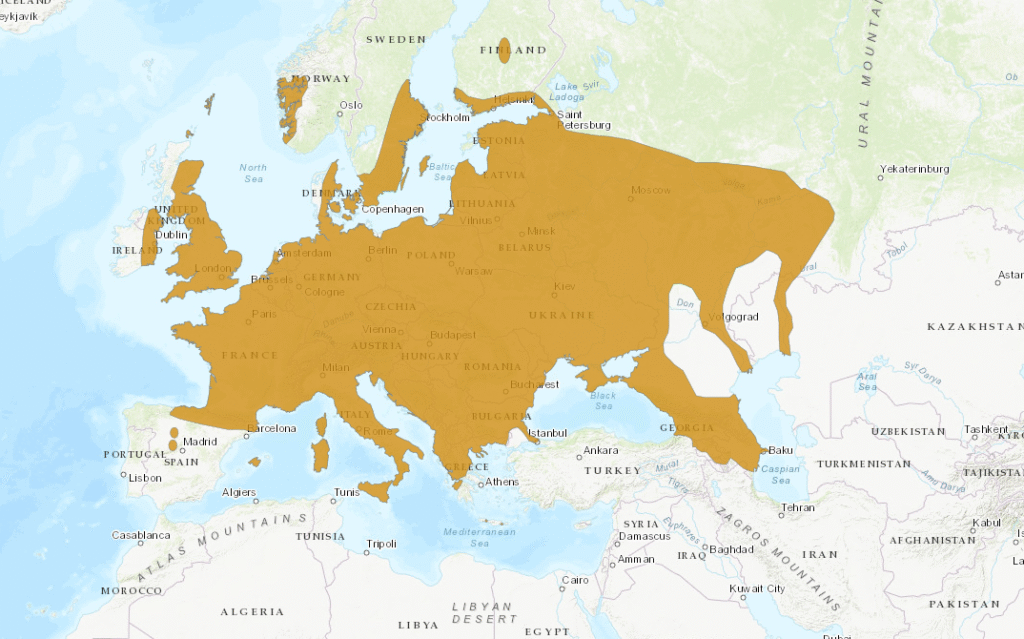

NATHUSIUS’ PIPISTRELLE (Pipistrellus nathusii)

Nathusius’s pipistrelle is one of Europe’s great migratory bats, and its presence in Jersey connects the island directly to continental flyways. Unlike the common and soprano pipistrelles, which are largely resident, Nathusius’s pipistrelle travels hundreds — sometimes thousands — of kilometres between breeding and wintering grounds. Its small size, just 6–15 grams, makes these journeys all the more remarkable. Jersey sits on the western edge of its European range, where records are still relatively scarce, but growing.

Taxonomy & History

The species was first described in 1839 by German naturalist Heinrich Kuhl’s successor, Paul Gervais, though it was named after Johann Nathusius, who first studied it in detail. For many years, Nathusius’s pipistrelle was considered rare and poorly understood. It wasn’t until the late 20th century, with the development of bat detectors and ringing programmes, that its migratory behaviour was revealed.

Ecology & Behaviour

Breeding populations are centred in northern and eastern Europe, while wintering grounds extend to southern France, Spain, and the Iberian Peninsula. During autumn migration, Nathusius’s pipistrelle travels along river valleys, coastlines, and across seas, including the English Channel. It roosts in tree holes and bat boxes, emerging to forage on midges and moths. In Jersey, it is detected acoustically at wetlands, reservoirs, and even offshore reefs, confirming its use of the island as a migratory waypoint.

Conservation

Globally listed as Least Concern (IUCN), Nathusius’s pipistrelle is nevertheless of growing conservation interest because of its long-distance movements and vulnerability to wind turbines, which intersect with its migration routes. In France, it is considered scarce and migratory, not abundant year-round. For Jersey, continued monitoring is key to understanding its role in European migration networks.

Research Notes

The European Bat Migration Project has been pivotal in tracking Nathusius’s pipistrelle across the continent, with ringing recoveries documenting journeys of over 1,900 km (for example, from Latvia to Spain). In the Channel Islands, its presence has been highlighted in iBats surveys and more recently in the Offshore Reefs and Bats Project. Local data suggest it is a regular, if still under-recorded, migrant through Jersey.

Fun Fact

In 2016, a Nathusius’s pipistrelle ringed in Latvia was found in Spain, a journey of nearly 2,000 km — one of the longest recorded migrations of any European bat.

Further reading

Alcade, J.T., Jimenez, M., Brila, I., Vintulis, V., Voigt, C.C., Petersons, G. 2020. Transcontinental 2200 km migration of a Nathusius’ pipistrelle (Pipistrellus nathusii) across Europe. Mammalia, 85(2), pp. 161-163.

Barratt, E.M., Deaville, R., Burland, T.M., Bruford, M.W. 1997. DNA answers the call of pipistrelle bat species. Nature, 387, pp. 138-139.

Dietz, C. & Keifer, A. 2016. Bats of Britain and Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Jennings, N., Jones, G. & Harris, S. 1997. Identification of British bat species by multivariate analysis of echolocation parameters. Bioacoustics, 7, pp. 189-207.

Mammifères de Bretagne, 2023. Fiches d’espèces: Pipistrelles communes et rares de Bretagne. [online] Available at: https://mammiferes-bretagne.fr/

Mayer, F. and von Helversen, O., 2001. Cryptic diversity in European bats: the Pipistrellus pipistrellus complex. Molecular Ecology, 10(5), pp.1235–1251.

Russo, D. & Jones, G. 2002. Identification of twenty-two bat species (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from Italy by analysis of time-expanded recordings of echolocation calls. Journal of Zoology, 258(1), pp. 91-103.

Vaughan, N., Jones, G. and Harris, S., 1997. Habitat use by bats (Chiroptera) assessed by means of a broad‐band acoustic method. Journal of Applied Ecology, 34(3), pp.716–730.

Working to protect and conserve Jersey’s native bat species through research, education, and community involvement.

Join our mailing list to receive updates about bat walks, training, and events.

2025 Jersey Bat Group. All rights reserved.